Warcraft Retrospective 29: Interlude: The Value of Mystery

Let’s catch a break from the fast-paced storytelling of Reign of Chaos, take a step back, and look at the big picture.

This story is not particularly novel or groundbreaking, not even by video game standards. If we judged games solely by the quality of writing and depth of characterization, I could easily name some games even from the same year that beat this game fair and square. Where Warcraft 3 excelled was presentation, and that was made this story and these characters so memorable and evocative.

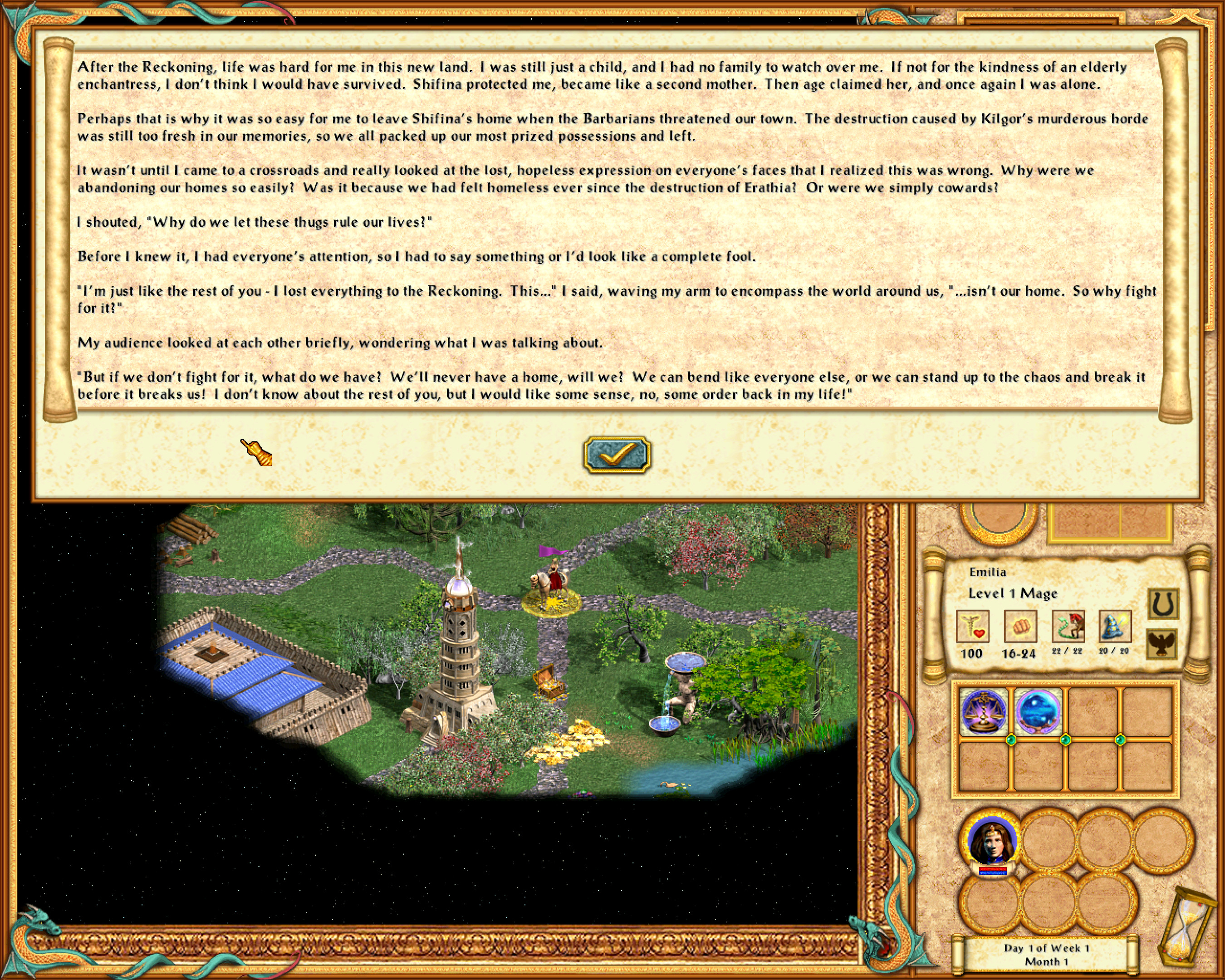

Yes, Heroes 4 has six campaigns with a novel-length story each, containing good twists and turns. But that storytelling is done through text throughout the missions and is almost completely divorced from the gameplay.

The strategy genre, whether real-time or turn-based, is inherently tricky to use as a storytelling medium because of the heavily abstracted gameplay. (Imagine trying to tell a character-driven story through a Civilization campaign!) It’s hard to make immersive cutscenes on a map where units and heroes are huge and buildings and trees are tiny.

And yet Warcraft 3 succeeded.

It succeeded by making its presentation as vivid and visceral as possible. Everything in this game, from units to buildings to the user interface, was crafted to give the impression of weight, of physicality. Menus are shaped like physical panels and slide down and up on chains that make a sound. The colors are bright and vibrant, helping compensate for the limitations of 2002’s 3D graphics. The visuals are all exaggerated, larger than life, with bulky armor designs and trees that shake when hit by a peasant’s axe. Powerful AoE abilities like Earthquake shake the screen. And the visual designs of units and buildings support the game feel in such a way that you rarely even need to look at the numbers: generally, the bigger and more menacing a creature looks, the more dangerous it is.

And the story is told through in-engine cutscenes and voice lines spoken through the missions that are short, snappy, and are neither too simplistic nor dumping an entire wiki’s worth of exposition on the poor player, providing just enough detail to understand the plot and the character motivations in their proper context.

Warcraft 3 is a comic book in game form. By the nature of its medium, a comic book allows less nuance than a novel and doesn’t have the cinematic fluidity of a movie, so it has to compensate through bright colors, bold character designs and exaggerated body language, as well as the ability to blend visuals and text together and have them support each other.

This is not that surprising, considering Chris Metzen is (or was) a big fan of comic books and cited them as one of the major inspirations for the Warcraft setting; for example, Sargeras was inspired by the fire giant Surtur from Marvel’s Thor, one of Metzen’s favorite comic book franchises.

Though we might sneer at Blizzard’s shallow characters now, this kind of immersive storytelling that makes as many players as possible to care about at least the broad strokes of the story and characters takes finesse, attention to detail, and many iterations of draft scripts and storyboards, and is very, very easy to get wrong. As an example of how an imitation of the Warcraft 3 approach can easily go wrong, consider Heroes of Might and Magic 5.1

The first mission begins with a five-minute-long cutscene, the first two minutes of which are a recreation of an in-game tactical battle between two no-name heroes that are never seen or mentioned again. Then we sit through three minutes of exposition consisting of three people standing still and talking, with shoddy camerawork, where the characters sit on their horses making weird hand gestures and casting random spells. The mouths of their world models don’t move, and since there are no animated portraits like in Warcraft 3, there is nothing to convey the idea that they’re actually speaking rather than somehow conversing telepathically. We hear random exposition about faraway lands that doesn’t matter to this mission in particular, all the while the player is shouting “get on with it already!”

The unit models don’t support the story either. The queen, at this point in the story, is supposed to be a noncombatant who was evacuated to the countryside for her own safety, and who only goes to war herself after learning that her husband is taking losses at the front — yet in the cutscene, before she’s told any of this, she is already mounted, fully armored, and holding a sword.

The best story in the world could be ruined by such clunky presentation. And unfortunately, Heroes 5’s story isn’t exactly brilliant either, to the point that there’s an abridged script website mocking it. It broadly copies Warcraft 3’s setup of “the demons are behind everything and everyone unites against them after you play each faction in order”, but fumbles it. The characters make nonsensical decisions, fall for obvious traps and obviously evil advisors, and use powers that are incredibly convenient at that one moment yet are not used or mentioned again.

The gameplay doesn’t support this story either. Because of how the stack mechanics in this game work, the heroes field enormous armies, yet their size is never acknowledged in-story. We spend two missions on pure padding, where the anti-hero protagonist, a former demon cultist on the run, conquers almost the entire elven kindgom because he needed a freaking ship, and as soon as he boards that ship, he leaves them alone. In the process he recruits these elves (because that’s how the gameplay works) to fight their own brethren with a unit they’re not yet supposed to have story-wise. Later in the story, after we switch to playing the elves, we get a whole mission solely dedicated to unlocking that unit. Sigh.

Not only that, but this is a turn-based strategy game where, quite often, in-game days pass with nothing happening from your perspective, with your actions that day being limited to moving your hero a bit farther through the map and clicking the “end turn” button. This makes fast-paced storytelling impossible and negates any sense of urgency instilled by the cutscenes.

Warcraft 3, in contrast, strikes a very delicate balance.

On one hand, it integrates the gameplay and the story as closely as possible in an RTS game, using a variety of map scripts and cinematography tricks to achieve this. On the other hand, it almost never forces silly gameplay tropes that undermine the seriousness of the story, and almost never treats gameplay abstractions as literally true.2

But also, I think one of the things to which Warcraft 3 owes its enduring popularity is one of its most important characters. And I’m not talking about Arthas, Thrall, or Illidan, but rather the world itself.

A Whole New World

Warcraft 1 took place within a single human kingdom. Warcraft 2 spanned a whole continent, and its expansion took us to the orc homeworld, Draenor.

Warcraft 3 expanded the world far, far beyond that.

There was a whole cosmos out there, a cosmic level conflict, ancient powers we knew almost nothing about: the Titans, the Burning Legion, and the Old Gods. Worlds beyond counting were being shaped, reshaped, and extinguished by forces beyond our puny mortal comprehension. Even of “our” world, it turned out we knew precious little; it was much larger than we thought, more ancient than we thought, and filled with a wider variety of creatures and cultures than we thought. It was full of untamed wilderness, ancient ruins, and forgotten dungeons. And dragons.

It was a perfect adventure-friendly world.

When I finished the Reign of Chaos campaign back at release, in 2002, I was awestruck, and what little was revealed of this expanded world sparked my imagination. We’ve been introduced to two mysterious, mostly uncharted continents: Kalimdor and Northrend. As far as I knew, they could contain anything. Races beyond our imaginings, hidden forest villages, natural wonders, abandoned Titan artifacts or superweapons, dragon lairs, goblin towns (there were goblins in Kalimdor already, after all, before the orcs even got there)… the list went on.

And I had questions about setting elements already revealed. Reign of Chaos revealed just enough to hint that there was more to the world, while leaving players hungry for details.

The night elves in particular sparked my interest. They were not an obvious copycat of an established fantasy race, which meant that the writers could go wild with them, and no assumptions could be taken for granted. And I had so. Many. Questions.

So far we’ve only seen two stands of night elf society: Sentinels and druids. Is that all there is? Are all women warriors and priestesses, and all men druids? Do they have civilians? If not, who makes them their armor, weapons, ballistae, and other wonderful toys? What do they eat? Do they eat? (For all I knew, they could be drinking moonwell water for sustenance.) Are there night elf settlements elsewhere, outside of the forested north of Kalimdor? How would they fare outside their home environment — for example, if they were to mount an expedition to another continent?

And for that matter, what did happen to the allied forces after the explosion of the World Tree? Reign of Chaos abruptly ended with a swarm of wisps destroying Archimonde, but even without him, the Legion and Scourge forces were large enough to crush the defenders anyway. Were they a keystone army?

I wanted to see Thrall and Jaina settle down in Kalimdor and learn more about it. I wanted to see more of Northrend, and to learn what happened back in Lordaeron after Archimonde’s death left a power vacuum. More about the plans of Arthas, Ner’zhul, and Kel’Thuzad, whatever they were.

Mysteries and a desire to learn answers to them are a powerful way to keep readers hooked, and fantasy writers know this. J.R.R. Tolkien, Ursula Le Guin, Brandon Sanderson, George Lucas and many others knew this and used it effectively. Often, a sequel to an already successful fantasy work was built upon answers to a mystery introduced in the original; for example, The Hobbit left the mystery of the Necromancer unresolved, but it was clear that any hypothetical sequel would deal with him somehow, and then The Lord of the Rings made him (revealed to be Sauron) the main antagonist, while tying it to a mystery so well-concealed that we didn’t even know it was there: the mystery of the origin of Bilbo’s ring.

But of course, mysteries, once established, have to be handled delicately. A badly handled mystery has the potential to not only ruin the specific work that fumbles, but retroactively poison previous works that run on that mystery, as well — if it makes you retroactively realize that the author had no idea what they were doing, or worse, if they did, but their intent all along was really, really bad.

Not All Mysteries are Created Equal

It’s important for fantasy writers to recognize the difference between two types of mysteries: those that are meant to be revealed later for a satisfying payoff, and those that never, ever, should be answered, because any answer would inevitably be less satisfying than no answer. And in the latter case, not giving answers is fine, and almost nobody will ask for them anyway.

In the Star Wars original trilogy, the Force was introduced as a mysterious spiritual… something that bound all life together and that Jedi could tap into through intense training and discipline. Even the Jedi themselves didn’t know what exactly the Force was, and they spent their entire lives figuring that out. And that was completely fine! Star Wars was never really about figuring out the nature of the Force, and it provided a nice mystical side to an otherwise materialistic setting. I don’t think there were many people who were dying to have the Force explained, and those who were probably just had their own headcanon explanations they were happy with.

And then came the first prequel movie, The Phantom Menace. The Force was reduced to microscopic organisms living in cells. Someone’s Force potential, it turned out, could be directly measured by taking a blood test and counting midi-chlorians. Even if you are one of these people who think everything in a spacefaring setting must ultimately be explainable in terms of science even if the characters don’t know the explanation, this was the wrong way to do it: too blunt, too “neat”, too reductive. It made a lot of people unhappy and was widely regarded as a bad move.

You should be particularly cautious about themes that matter to a lot of people in real life. In our world, there’s no universal agreement on gods and the afterlife.3 In fantasy worlds that are patterned more or less on our own, often the characters aren’t certain what happens after death, and if the afterlife became known and explored and entered the public consciousness, if people could rely on getting into a specific afterlife in the same way as they can rely on the sun rising, coal burning, rivers flowing and things falling down, it would change the world into something completely unrecognizable and hard to empathize with. And if furthermore the afterlife was revealed to be a clockwork, mechanistic system where the apparent gods were actually all robots, such a setup would be unlikely to appeal to anyone but the most power-gamery of D&D munchkins.

For an opposite example, if you have a mystery in a hard science fiction setting where all apparent gods and magic so far have turned out to be sufficiently advanced alien science, then revealing the mystery to be actual magic is also going to alienate a lot of people. The bottom line is: know your genre, and know your audience.

On the other hand, if you do intend to eventually reveal a mystery, then you, as the writer, need to know the answers far, far in advance. The audience expects you to know all the important things about your setting, even if you actually don’t. If you keep teasing the audience but never actually deliver any answers, instead just digging yourself deeper and tangling the knots ever further — as happened to The X-Files and Lost — then the audience will eventually stop following your work, because they’ll realize that you have no long-term plan, no climactic reveal that everything is building up to, and instead are just making it up as you go along.

And when you do pull the curtain and present the answers, they better be satisfying and thematically fit into the rest of the work. If your unfathomably-advanced ancient race of mecha-Cthulhus is doing something that seems strange but does, according to them, have a motivation that we cannot comprehend, then the last thing you want is to reveal that their motivation is not only very much fathomable, but runs on circular logic and is disproven by plot developments that took place just a few scenes ago.

Or perhaps the answer will turn out to be not so much outrageously bad as simply boring and not worth the hype that was being built up. An army of unrelenting ice creatures with unclear motivations, an ever-looming threat on the horizon that’s getting closer and closer? Yeah, they’re just former humans corrupted and turned against their own as revenge that backfired on their creators. What do they actually want? To kill everyone, apparently. And how are they defeated? By a rogue sneak attack on their leader that destroys them all. Yawn.

Underexplaining, overexplaining, and giving unsatisfying explanations are all ever-present dangers to worldbuilders. I’ll touch this subject again, much much later, when we get to the Chronicle books and examine the common claim that they “overexplained the mystery of the Titans”.

The Mystery is Dead, Long Live the Mystery!

After all these examples of botched mysteries, it’s only fitting that I give an example of mystery-driven writing done right.

I will turn, once again, to Final Fantasy XIV. I’ve talked about it before, but it does so many things right as a story-driven MMO that we’ll keep revisiting it, alongside other modern MMOs, once we reach World of Warcraft.

Mysteries and a search for answers are at the core of FFXIV storytelling. From the very beginning of the now-defunct version 1.0, and throughout the expansions of the rebooted game, the player, alongside their character, is assaulted with seemingly unrelated puzzle pieces. A strange voice from heavens that sings a song and chants “Hear. Feel. Think.” to you. A pantheon of twelve gods that seem to be more than they appear. Summoned physical gods that you’re tasked with fighting before they drain the land of all life. An expansionist empire. An ancient conspiracy of shadowless cultists who seem to be manipulating everything from behind the scenes…

And over the course of the long, long storyline that began in 1.0 and ended in 6.0, you, alongside your character, get answers to many of these questions, and many of them turn out to be not what you expected. It’s so integrated into the plot that it focuses on an order of scholars that your character works for as a professional monster-slayer. They seek answers, make theories, test them with their magical science, and eventually, bit by bit, understand more of the nature of the world and its history, until the pieces of the puzzle begin to fall together into a picture that involves, among many other things, an ancient fallen empire and an even more ancient fallen society that nobody knew even existed.

Your companions stumble, hit roadblocks, and occasionally their existing theories are proven wrong by new discoveries that change everything. By the end of the 6.0 storyline, which finishes the game’s first and (as of this writing) only mega-arc, most of the world’s cosmology is revealed, and the revelations tie into the epic conclusion of the story. But every individual expansion strips away the mystery only a little and raises new questions, leaving the player eager to know more.

As an example, here’s the list of open questions (MASSIVE SPOILERS) that I wrote after finishing the first expansion, Heavensward. Most of those questions were answered by later expansions, and some turned out to be based on invalid assumptions. But now, as the 7.0 expansion, Dawntrail, is about to launch, there is still a lot we don’t know about the FFXIV universe, and neither do the characters.

We know that the answers we got were not planned from the start. The authors of the revelations had to work with the clues and themes already given and put them in a new, unexpected context that made it seem like it was planned in advance all along. Generally speaking, it’s a very very risky approach, and FFXIV just barely got away with winging it. In the hands of less skilled writers it would have spelled disaster.

And this, I think, is a healthy approach to mystery-driven storytelling. Give the audience the answers, eventually — in a way that matters to the story and gives it depth, instead of just giving answers for the sake of giving answers — but introduce new mysteries in the place of revealed ones. After all, the more you know, the more you know you don’t know.

What’s Next?

Playing a Blizzard RTS followed immediately by its expansion is a weird experience. The original Starcraft ended with a protoss campaign, and then its expansion, Brood War, opened with a protoss campaign, which meant that if you were playing the original game and the expansion together, you’d be stuck with the protoss for eighteen missions in a row.

Warcraft 3 follows the same pattern, which was one of the reasons I decided to write an intermission post before heading into its expansion, The Frozen Throne.

Next up: more night elves! We’ll address one of the loose threads of Reign of Chaos by finding out what happened to Illidan. The guilty will suffer! (Eventually.)

Screenshots from Heroes of Might and Magic 4 and Star Wars: The Phantom Menace.

-

Now, gameplay-wise 5 is easily one of my two favorite games in the HOMM series, along with 4, but oh boy is the story just unintentionally hilarious in a bad way. ↩

-

With just a few exceptions. Looking at you, Daughters of the Moon. ↩

-

I have strong opinions on this matter, but I’m keeping them out of this blog. ↩

Leave a Comment