Warcraft Retrospective 5: Tides of Darkness, the Manual

Last time, we ended on Warcraft 1’s multiple-choice finale. Either the orcs conquered Stormwind Keep, or the humans drove them back into the portal they came from.

This presented a problem for any future storytellers. When a game has multiple mutually exclusive endings, the writers of its sequels typically declare a single ending canon and proceed from there. And usually, they choose the ending where the good guys win.

In Star Wars, there are games where the player can make the protagonist fall to the dark side and possibly even take over the galaxy, such as Knights of the Old Republic and Jedi Knight: Dark Forces 2. But other Star Wars stories that follow the events of these games make these endings non-canon. The first expansion to Neverwinter Nights 2, Mask of the Betrayer, assumes that the player defeated the big bad instead of joining him. Sure, these are all RPGs or shooters, but there are strategy examples as well. For example, Heroes of Might and Magic 2 tells the story of a war for succession between two heirs to the throne, one good and the other evil, and the sequel continues from the victory of the good brother.1

The writers of Warcraft 2 did something that was not entirely unprecedented, but still very rare to see in video games. They continued the story from the ending where the bad guys won.2

Seeds of the Sequel

After the success of Warcraft 1, Blizzard began brainstorming the sequel. Wanting to subvert player expectations, they considered different ideas, one of which was having orcs invade the modern world; they even brainstormed cinematics with dragons battling fighter jets. They rejected this idea pretty soon and decided to keep Warcraft in the fantasy world of the first game.

Interestingly, the idea for a crossover with the modern world came from Blizzard co-founder Allen Adham, and artist Stu Rose fought him for it. In the end, Adham yielded. It’s notable because the people in charge of the game realized that their “awesome” idea would do the budding franchise more harm than good, and rejected it early before sunk cost became an issue; and that it was better to flesh out the setting they already had than to subvert expectations for the sake of subverting expectations.

So the plans were revised.

The new vision of the project was still ambitious. Not only did the designers want to have naval and aerial units, they also wanted to move beyond the strictly one-on-one battles of the first game. On multiplayer maps, players could now have allies, as well as multiple enemies. The same was true of the campaign. This necessitated introducing more sides into the conflict, both in gameplay and in lore.

And to do that, they needed to expand the world.

Enter Chris Metzen

This series will turn a lot more critical later on as we move to World of Warcraft and its expansions. Generally I will aim to avoid naming and shaming. While I have my own theories on who wrote what3, we don’t truly know the full story of Blizzard’s creative decisions, and likely never will. The purpose of this series is to examine the franchise as a whole, not to cast blame. But Chris Metzen’s influence on Warcraft cannot be overstated.

In Warcraft 1, Metzen was just one of several artists. He joined the project late in development, and we find his name near the bottom of the credits, as one of the manual illustrators. At that time, he was twenty years old, and he had a knack for coming up with interesting crazy ideas and pitching them to the rest of the team. This caught the interest of the higher-ups, who, to Metzen’s surprise, just outright put him in charge of Warcraft 2 story and design.

Opinions on Metzen as a writer are polarized. Personally, I think different writers have different strengths and weaknesses, and the successful ones leverage their strengths while avoiding drawing attention to their weaknesses. Furthermore, when multiple writers work as a team, there can be division of labor: one writer can pitch novel, big-picture, attention-grabbing ideas, and another can refine them with deep dialogue and descriptions with attention to detail.

I think Metzen is a great “idea guy”. He’s the Russell T Davies of Warcraft, in that he comes up with wild, crazy, but easy to understand concepts that immediately stand out, giving the setting its unique flavor, but doesn’t seem to be particularly interested in the minute details, leaving them to other writers to flesh out. He builds wide, not deep. The end result is that when he’s given free rein, the stories are full of epic and memorable moments, but are puddle-deep, whereas when detail-focused writers work on the setting without him, the result is fulfilling but relatively bland, missing that special ingredient.4

Let’s see what turns the setting took with him in charge of the lore.

Legends of the Land

Unfortunately, the only version of Warcraft 2 that Blizzard sells these days is Battle.net Edition, which includes both the original game (Tides of Darkness) and the expansion (Beyond the Dark Portal). This edition has a single manual, which is available on the Blizzard website for free. Fortunately, the expansion-specific section in the manual is separate, so I’ll review it later when we get to that.

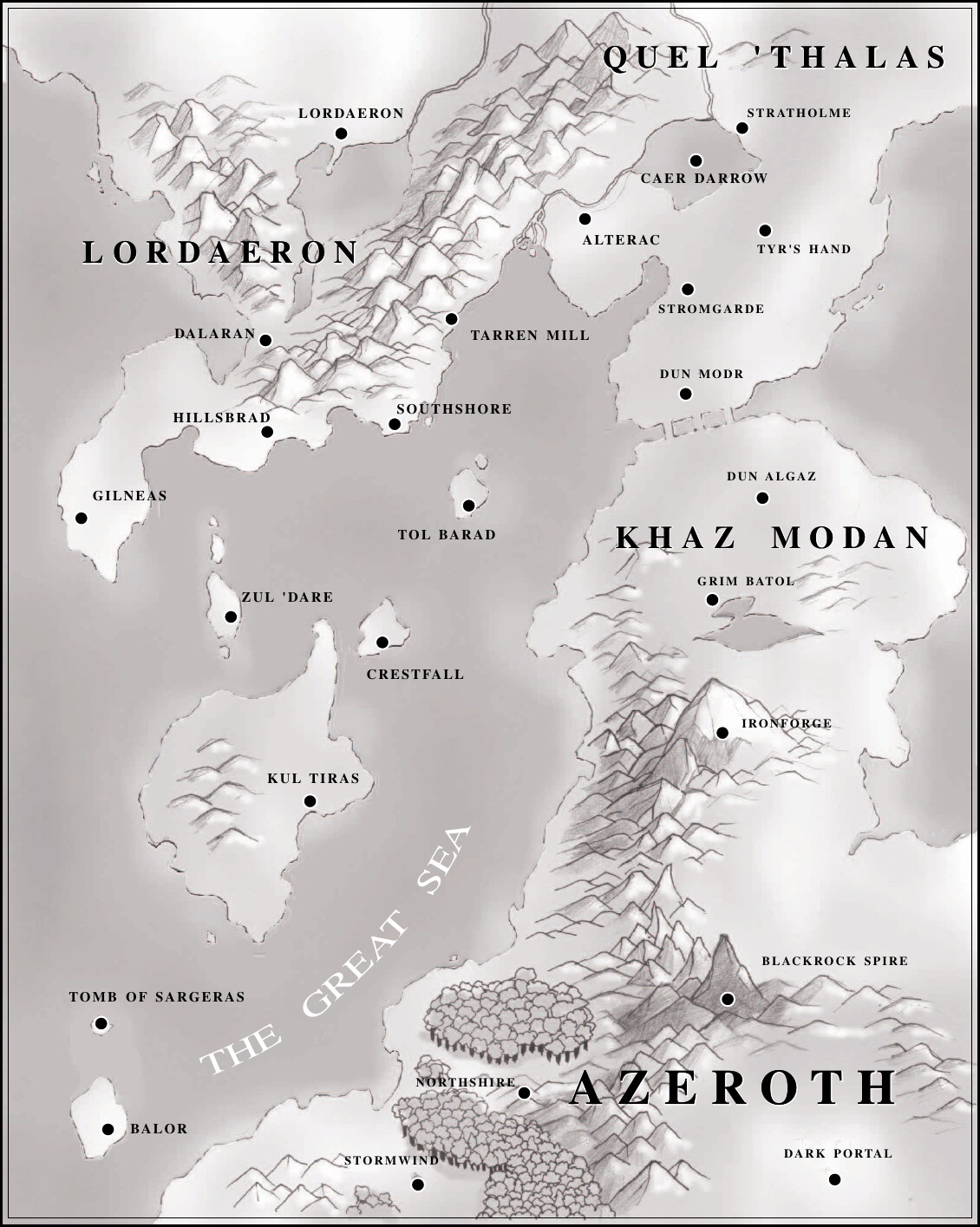

Unlike Warcraft 1, the Warcraft 2 manual isn’t split in two. Before delving into faction-specific lore, it begins with some shared sections: Legends of the Land, Creatures of the Land, Resources of the Land, and Places of Mystery. And a map!

The “Legends” of the Land” section features brief descriptions of six lore figures: Sir Anduin Lothar, Gul’dan, Sire Uther Lightbringer, Cho’gall, and Zuljin [sic]. There’s some real meat here:

- We learn Lothar’s first name.5 Following Llane’s death, Lothar took the people of the Kingdom of Azeroth by sea into Lordaeron, and was declared Regent Lord. This writer, unlike the Warcraft 1 campaign writer, understands what a regent is. It seems, however, that the Warcraft 1 manual writer also took part in writing this manual, as both manuals are fond of using the phrase “all but killed” to mean “left on the brink of death, but alive”.

- Zuljin is a “feared, rogue Troll” known for raiding elven villages. We’re introduced to both elves and trolls here, in the same breath.

- Cho’gall is the first of the ogre-magi, chieftain of the Twilight’s Hammer clan, and an ally of Gul’dan in the Shadow Council.

- Uther is a young apprentice of Archbishop Alonsus Faol, who was the leader of the clerics of Northshire and fled to Lordaeron, where he introduced the teachings of the clerics to the knights of Lordaeron and thus formed the paladins of the Silver Hand. That Uther is called “young” here is… interesting, considering his grey hair in Warcraft 3, only sixteen years later.

- Finally, Gul’dan is a powerful warlock and an apprentice in “the arts arcane” to the daemon Kil’jaeden. He is the mastermind behind the Horde and the Shadow Council. He wants to obtain the secrets of the Tomb of Sargeras, and the necrolytes, ogre-magi, and death knights are all his creations.

There is a lot to unpack here, so I’ll say more when we get to human and orc lore.

The “Places of Mystery” section talks about:

- The Runestone at Caer Darrow, an ancient monolith erected by the elven druids and desecrated by Gul’dan and his ogres to create the ogre-magi.6

- The Tomb of Sargeras, which is “rumored”7 to contain the remains of the ancient daemonlord Sargeras defeated by Guardian Aegwyn [sic]. Medivh, her son, promised to give away its location to Gul’dan in exchange for the destruction of Azeroth8, but was killed before he could do so. Now Gul’dan wants to find it.

- The Portal, through which the orcs originally invaded the world, is still there and is draining the land around it, turning it into “barren soil the color of blood”. This needs to be stopped before it consumes the entire world.

This is interesting. Remember that Warcraft 1 left us two mysteries: Medivh’s mysterious dark powers and motivation, and the identities and role of the Shadow Council. We get some answers here. We know from the first game that it was Medivh who brought the orcs into this world. Now we know why: he wanted the Kingdom of Azeroth destroyed (for reasons yet unexplained) and struck a deal with Gul’dan, the mastermind behind the Shadow Council, who agreed to invade in return for information about the Tomb of Sargeras.

This is the first time we see the name “the Horde”, rather than the plural “orcish hordes” from the first game.

Finally, there’s the map, which reveals that the entire setting of Warcraft 1 was a small patch at the south of a yet-unnamed continent. There are a lot more nations to the north, as well as a few islands strewn across the sea, which makes sense for a game with a heavy focus on naval combat. The setting has been tailored to fit the story, as much of the campaign takes place in that giant gulf south of Lordaeron.9 This makes sense; there’s a reason One Piece doesn’t take place on a giant supercontinent.

It seems we’re following the ending where the orcs won, but where the Lothar and Medivh missions of the human campaign still happened. Let’s dive into follow-up lore, starting with…

The Human Section

As before, we open with a tale by an unreliable narrator. This time it’s Aegwyn, Medivh’s mother.

This is a huge expansion on Warcraft 1 lore. We get the names of both Medivh’s mother and father, as well as the reason why Aegwyn (with one N for now) gave birth to him in the first place. She was the Guardian of the Order of Tirisfal, appointed to protect the world from the mysteries of the Great Dark Beyond10 and the horrors of the Twisting Nether. She decided to bear a child to whom she could pass her powers.

However, unprepared to deal with his PHENOMENAL COSMIC POWER, Medivh fell into a coma, in which he lay for six years. During that time, his soul was forever twisted by the evil of the Twisting Nether. Hungering for more power, he turned to necromancy, struck deals with daemons, and eventually, discovering the orcs and their homeworld, struck the aforementioned deal with Gul’dan. We get a reason why Medivh wanted the Kingdom of Azeroth gone: it was the only thing that threatened his rise to power.

Medivh opened “the first of his unnatural Portals” (implying there were more?!) to let the orcs into Azeroth. What follows is a brief recap of the events of Warcraft 1. Medivh was killed, but the orcs were nonetheless victorious, sacking Stormwind Keep and killing King Llane. However, Lothar led the survivors across the sea, setting the stage for…

The Alliance of Lordaeron

Alarmed by the orc threat, King Terenas of Lordaeron gathered “a council of delegates from each of the seven kingdoms under his rule”. It’s strange that all seven kingdoms are described as being under his rule when it’s immediately contradicted by the following text. Even the dwarves of Khaz Modan and the elves of Quel’thalas [sic] came in, with the three races looking past their old grudges.

This is big. We learn that this world is inhabited by more races than just humans, and that there are many kingdoms across it. This immediately changes the setting from a proto-Diablo to something more akin to Dungeons & Dragons.

Meet the seven kingdoms!11

- Azeroth. Blue, led by Regent Lord Anduin Lothar. Their defining trait is being refugees seeking to retake their homeland.12

- Lordaeron. White, led by King Terenas. Their defining trait is religion.

- Stromgarde. Red, led by Thoras Trollbane. Their defining trait is martial prowess from a long history of war with the trolls.

- Kul Tiras. Green, led by Lord Admiral Daelin Proudmoore. Their defining trait is their navy, both merchant ships and warships.

- Gilneas. Black, led by Genn Greymane.13 Their defining trait is not joining the Alliance.

- Dalaran. Violet, led by the Kirin Tor (no named characters). Their defining trait is magic power and knowledge.

- Alterac. Orange, led by Lord Perenolde. As the weakest of the human kingdoms, their defining trait is fear of being steamrolled by the Horde.

And lifted straight from D&D, you get your typical forest-dwelling elves, subterranean dwarves, and steampunk inventor gnomes. None of them have any named characters.

The unit roster has undergone some changes. The archers are now elves, the mages come from the Violet Citadel of Dalaran (but oddly, they’re also described as one-students of the Conjurers from the first game). Instead of clerics, we have paladins, who in this game are upgraded knights. The dwarves contributed demolition squads and gryphon riders, and the gnomes built flying machines.

Finally, there are the naval units, most which require an additional, third resource: oil. These are the oil tanker, which is used to build oil platform; the elven destroyer, transport, battleship, and gnomish submarine. We have a weird mixture of sailing ships and more technological ones, and there’s no explanation what the sailing ships need oil for.

There’s not much to say about the buildings, except that lumber mills are now constructed by the elves (who are motivated by “seeking insight into the mysteries of the great Ironwood trees of Northeron14”), and churches still have crosses on them, but unlike in Warcraft 1, there is no mention of God. It’s unclear whom or what the human religion actually worships.

This is big. We’ve jumped from a pseudo-medieval setting into one where sword and sorcery coexist with steampunk technology. There are no firearms yet, but foundries, oil refineries, flying machines and submarines are already in. Next time someone says WoW ruined Warcraft by introducing technology, you can remind them that technology has been part of the setting almost from the start. The difference is one of degrees, of course; this is at best Industrial Revolution era tech, not spaceships and laser guns.

The Orc Section

The narration here is done by Gul’dan, Chieftain of the Stormreaver Clan and Initiate of the Seventh Circle of the Shadow Council. As expected, he’s very haughty and boastful throughout the story, which provides additional context for the orc invasion back in Warcraft 1.

The gist of it is thus. The orcs were always a violent race reveling in conquest. They conquered the whole world and exterminated the draenei, whom they regarded as a weak race, and then fell into apathy and infighting as there was nothing more left to conquer. Gul’dan himself was a shaman15 student of several teachers, including Ner’zhul, and his talent for channeling the dark powers of the Twisting Nether got him the respect of his peers. Ever hungering to unlock the secrets of the cosmos, Gul’dan made contact with the daemon Kil’jaeden, who went to tutor him personally.

The orcish religion worships their ancestors. Reaching out into the Twisting Nether into his mind, Gul’dan discovered that the spirits of the ancestors do indeed linger on and watch over the living “in hope of finding some means of escape from their lifeless torment”. He sought a way to control them, and thus began his foray into the art of necromancy.

If this was modern WoW, I would balk at the workings of the afterlife being revealed so casually. However, this story is told to us from the point of view of Gul’dan, a megalomaniac obsessed with power and a very unreliable narrator. If later writers wanted, they could easily say he was mistaken or lying, perhaps to justify his own ambitions to himself and others. Perhaps the spirits of the ancestors were in fact at peace, but he called it torment so he could justify binding them to walking corpses as a way of “freeing” them from this torment. The point is that the device of the unreliable narrator is clearly telegraphed here, instead of being contrived by the writers retroactively.

At any rate, upon his discovery, Gul’dan gathered other warlocks and taught them necromantic rituals. It’s important to note that these other warlocks already existed; Gul’dan wasn’t the first orc warlock, but he was their first necromancer. Together, the warlocks formed the Shadow Council, which secretly took control of the Horde through subterfuge and mind control, and began training the necrolytes.

However, without new lands to conquer, the Horde was still volatile and in danger of turning on itself. It was at that time that Gul’dan’s warlocks, but not Gul’dan himself, began to feel a certain presence in their dreams. Gul’dan questioned Kil’jaeden about this force, but to his surprise, the daemon reacted with fear. When the presence contacted Gul’dan himself, it revealed itself as Medivh, a human sorcerer showing him a vision of a lush, peaceful world, and an ancient power buried deep beneath the ocean.

Gul’dan shared his vision with the Shadow Council, and together they worked to open a rift to this new world. The first attempt to assault Stormwind was led by Cho’gall and Kilrogg; it ended in disaster, with the orcs fleeing from the kingdom’s knights, and the two leaders blaming each other for the failure. Then, Gul’dan and the Shadow Council installed Blackhand as a War Chief the orcs would respect.

Medivh appeared in a vision again, promising to reveal the location of the Tomb of Sargeras to Gul’dan in exchange for the orcs destroying his enemies — the Kingdom of Azeroth. Gul’dan knew Sargeras was the daemon lord who taught Kil’jaeden himself. The regrouped Horde under Blackhand had more success, with Garona assassinating King Llane, but before it could triumph, Gul’dan sensed that Medivh was assaulted in his tower and mortally wounded. Gul’dan attempted to extract the knowledge of the Tomb from the dying sorcerer by force, but the psychic backlash flung him into a coma that lasted a few weeks.

Gul’dan awoke to a completely changed Horde. In his absence, Orgrim Doomhammer — retroactively revealed to be the orc player character of Warcraft 1 — overthrew Blackhand as War Chief, captured and razed Stormwind Keep, and tortured Garona to reveal the existence and location of the Shadow Council, which Orgrim then executed.

A weakened Gul’dan was brought to the new War Chief and, being in no position to resist, pretended to submit to him. To prove his feigned loyalty, he sacrificed all his necrolytes to bind the spirits of the Shadow Council into the corpses of the slain knights of Azeroth, raising them as death knights. He also deceived Orgrim into believing that Blackhand’s sons Rend and Maim were plotting against him, prompting him to disband the raiders.

Now, Gul’dan is biding his time. He has formed a clan of his own, the Stormreaver clan, and is waiting for the moment when he can discover the Tomb of Sargeras and strike back against Doomhammer.

The Orcish Clans and Their Allies

There’s not much I can say about the orcish clans at this point, as their identities are barely defined. There are seven of them, the same as the number of the human kingdoms, and they use the same seven colors.

- The Blackrock clan (red), the military backbone of the Horde. Led by Orgrim Doomhammer, who the manual notes is also known as “the Backstabber”.

- The Stormreaver clan (blue), loyalists led by Gul’dan.

- The Twilight’s Hammer clan (violet), loyal less to the Horde itself and more to the idea of universal annihilation. Led by Cho’gall the ogre-mage.

- The Black Tooth Grin clan (black), charged with guarding the Portal and named for the practice of knocking out one tooth as a sign of loyalty. Led by Rend and Maim, the sons of Blackhand, who may yet get an opportunity to avenge their father.

- The Bleeding Hollow clan (green), in charge of the occupation of Khaz Modan. Led by Kilrogg Deadeye.

- The Dragonmaw clan (white), who used shamanistic magiks (sic!) to bind the Dragon Queen Alexstrasza16 to their service, forcing her to lay eggs for the Horde’s use. Led by Zuluhed the Whacked.

- The Burning Blade clan (orange), less of a clan and more of a force of unstoppable rage that attacks even fellow orcs. No leader.

This is pretty basic. It won’t be until later lore that the clans will be fleshed out with customs of their own.

The orcs have also allied with the trolls, ogres (from whom Gul’dan created the ogre-magi), and goblin alchemists, who provide the Horde with zeppelins and sapper teams armed with explosives. As before, everything but the spells has exactly the same stats as the corresponding Alliance units and buildings. There is some interesting lore to be found here:

- The counterpart to the human Farm is the Pig Farm, where captured wild boars are bred for food.

- Dragons are native to northern Azeroth (which, at this point, still refers to the southern human kingdom that we know today as the Kingdom of Stormwind).

- Troll lumber mills are created from hollowed-out ironwood trees. The trolls have invented their own unique method of harvesting lumber: “By treating a group of trees with a volatile alchemical solvent, the Trolls can deaden and weaken large sections of wood. Though it is extremely hazardous to Peon and earth alike, this site makes the process of cutting lumber more efficient.”

- The Dragon Roost is where Alexstrasza is kept in chains by the Dragonmaw clan. It’s not explained how you can build more than one.

- The Horde counterpart to the gnomish submarine is not, as it could be expected, a goblin submarine. Instead, they use mind-controlled giant sea turtles as improvised submersible ships crewed by goblins.

- Baseline ogres are stupid and unwieldy because of the conflict between their two heads, but ogre-magi combine the brute strength of ogres with intelligence and cunning, which is what makes them so dangerous.

Some Thoughts

This. This is what good worldbuilding looks like.

The writer of the Warcraft 2 manual successfully takes one of the sequel hooks left by Warcraft 1 — the orcs have taken over Stormwind and are looking for new lands to conquer — and its unresolved mysteries, namely Medivh and the Shadow Council. It then massively expands the scope of the world, more so than perhaps any other installment in the Warcraft franchise save Warcraft 3, and recontextualizes the entire conflict of the first game in a way that makes sense in hindsight.

The reason I have devoted so much attention to the Warcraft 2 manual is that many lore concepts that appear in later games and stories take their origin here. Gul’dan, Kil’jaeden, Sargeras, the Twisting Nether, the Guardians of Tirisfal, the Seven Kingdoms, Quel’Thalas, Ironforge, and, of course, the very idea of the Alliance and the Horde instead of just humans and orcs — though, of course, it’s a very different Alliance and a very different Horde than the ones we see in modern Warcraft.

We’ve gone from orcs from a nondescript world invading a nondescript faux-medieval human kingdom to a “beta” version of what we now know as the Eastern Kingdoms. Furthermore, the entire tone of the setting is changed. Instead of demonic orcs wielding the power of Hell versus God-worshiping humans in a proto-Diablo-esque world, we now have something aesthetically closer to Dungeons & Dragons.17 The Alliance consists of traditional D&D “protagonist” races: humans, elves, dwarves, and gnomes. The Horde, meanwhile, is a coalition of traditional D&D “monster” races: orcs, trolls, ogres, and goblins. There’s no moral ambiguity here (yet); the Alliance is clearly intended to be the good guys here, and the Horde the bad guys. This will later change.

But what’s even more fascinating about the Warcraft 2 manual is how it hints at a larger world. The Great Dark Beyond is filled with countless worlds, as well as cosmic mysteries beyond current mortal comprehension. The daemons are out there somewhere, and seem to have a teacher-student hierarchy. This world has a past; though it’s only hinted at in broad strokes, we know that there is a history of past grudges between the humans, dwarves and elves, as well as Guardian Aegwyn’s defeat of Sargeras. Finally, the orcs had been conquering their world for centuries, and we don’t yet know anything about their old enemies, the draenei. This, again, reminds me of the original Star Wars movie and the way it hinted at a much larger galaxy than the few planets we saw on screen.

We’ve got answers to mysteries, but we’ve got new mysteries in their stead. As it should be.

If I were to nitpick, I think there are some obvious cases of gameplay-driven lore here. The manual writer took too much time explaining what didn’t really need explaining, like the absence of clerics, warlocks, necrolytes, and raiders compared to Warcraft 1. I don’t think most players would blink twice if the units were simply missing in this game with no explanation. The seven kingdoms and the seven orcish clans exist pretty much to give some flavor to your multi-colored allies and opponents in this game, though some do get involved in the plot, and they turned out to be good additions to the lore that have since been greatly fleshed out and gained distinct identities in their own right.

Next up: the human campaign!

-

There are, of course, exceptions; of particular interest is the approach of XCOM 2, which, not wanting to invalidate the triumphant ending of the first game, continues the story from the game over state, where the aliens won and took over the world. ↩

-

Recall that in the story of Warcraft 1, the orcs were basically a living demonic plague. You could, if you wanted, make a subversive story about how they were unfortunate victims of their nature, but this is early Warcraft, which is very black and white. The orcs were very clearly intended to be the villains of the first game. ↩

-

For example, everything involving the First Ones and Zereths. ↩

-

The same, in my opinion, is true of Russell T Davies. ↩

-

Warcraft 2 lifted quite a few things straight from The Lord of the Rings, but the name Anduin (“long river” in Sindarin) is by far the most blatant example. ↩

-

This particular bit of lore has since been retconned beyond all recognition. ↩

-

The writer of the Warcraft 2 manual liked the word “rumor”. All rumors mentioned in the manual are completely correct, at least in the light of lore as it existed back then. ↩

-

The kingdom, not the world. Remember, the world is still nameless. ↩

-

Known in modern lore as Baradin Bay. Later lore retconned all those islands to be west of the continent. ↩

-

Presumably she doesn’t mean the vacuum of space. It seems that “the Great Dark Beyond” here is meant to be some kind of counterpart to D&D’s Astral Plane, not physical outer space. ↩

-

They’re most probably not a reference to the Seven Kingdoms of Westeros in A Song of Ice and Fire, whose first novel wasn’t even published until the following year. ↩

-

This will be important later. ↩

-

This is an amusing unintentional example of a prophetic name. It will be a long time until worgen will be invented, let alone be associated with Gilneas. ↩

-

Not much is known about Northeron except that it’s one of the dwarven lands, but this implies it’s next to the elven lands. It was probably meant to be Northern Lordaeron before the Cataclysm developers said it was part of the Twilight Highlands. This is supported by this early WoW map sketch. ↩

-

This is the first reference to the orcs practicing shamanism. ↩

-

Her name is spelled as “Alexstraza” twice and as “Alexstrasza” twice in the Tides of Darkness manual, making it unclear which version is correct. The Beyond the Dark Portal manual uses only the latter spelling. ↩

-

With caveats that deserve a separate post. I will get to that before we move to Warcraft 3. ↩

Leave a Comment