Warcraft Retrospective 39: The Feel of Warcraft

And so we have traced the shaping of the Warcraft setting as we broadly know it: from a barely defined pseudo-medieval kingdom beset by savage evil alien invaders to a large, sprawling world of at least three continents1 populated by many different races, with a history stretching back over ten thousand years, in a universe full of other worlds, where mortals are but ants compared to enigmatic cosmic forces, from the seemingly benevolent Titans to the omnicidal Burning Legion.

It’s been a wild journey, and now that we’re done with Warcraft 3, which formed the foundation of the modern Warcraft setting, we can finally answer the question: What is that much-lauded feel of Warcraft? What is it that gives Warcraft its distict flavor, separating it from the likes of Dungeons & Dragons and other fantasy games, both tabletop and computer, that came before and after it?

What follows is merely my interpretation, which, of course, I don’t claim to be authoritative. Like I said long ago, Warcraft means different things to different people.

The Three Pillars of Warcraft

When discussing the feel of Star Wars, Shamus Young spoke of the three pillars supporting that setting: the world of the Force (Jedi and Sith), the world of politics (of queens, senators, empires and alliances), and the seedy underworld (of criminals, mercenaries, and bounty hunters). Similarly, I think we can speak of three pillars supporting the Warcraft setting:

- War. This was largely the sole pillar of Warcraft 1 and 2, and to some people it’s still the main appeal of the franchise. This is the war where massive armies clash in epic battles that decide the fate of whole continents, if not the whole world. This pillar is associated with great military leaders like Lothar and Orgrim Doomhammer. Wars in Warcraft can be fought between established factions like the Alliance and Horde, or against an evil threatening to destroy the world, like the Scourge and the Burning Legion.

- Exploration and adventure. Azeroth is a big world full of unexplored untamed wilderness, and its civilizations rely on pioneers, pathfinders, and sellswords to push their influence into the vast expanse separating the settlements. Anything can be lurking in the blank spots of the map, from small barbarian tribes to ancient vaults to eldritch monsters sealed away by the precursors. Rexxar’s campaign is an example of a Warcraft story where exploration takes an important part, as are many outdoor activities in World of Warcraft.

- Cosmic lore. This is the domain of barely comprehensible cosmic forces like the Titans, Old Gods, and Burning Legion, who clashed with each other before this world was even shaped. Compared to the vastness of the Great Dark Beyond and the Twisting Nether, Azeroth is just a tiny blue dot floating in the cosmos, and no matter how deeply we delve into cosmic lore, we will only scratch the surface. Unlike H.P. Lovecraft and friends, however, cosmic stories in Warcraft are not marked by utter hopelessness; the world can be saved, if at a great cost.

Individual characters and factions in Warcraft do not need to fall squarely into one pillar. For example, Brann Bronzebeard2 is a famed dwarven explorer who wrote much of the description of the lands in the Warcraft RPG, but his primary interest is learning about the Titans and their effect on the world and its races — which means he’s both a trailblazer and a researcher of cosmic lore.

I strongly suspect that different players have their own favorite pillars, which colors their perception of different Warcraft media.3 Some players swear by the Alliance–Horde conflict, while others consider it a millstone dragging the franchise down. Some love long-winded introductions to new lands and their inhabitants, while others find them a waste of time and a distraction from what they’re really after. This, unfortunately, makes it hard for players in different camps to find common ground in evaluating the quality of Warcraft media.

Alice: Dragonflight was boring. Everyone was friends, it was World of Peacecraft, and they defanged both centaurs and dragons into peace-loving goodies-two-shoes. I preferred Battle for Azeroth, which had a real war with real stakes.

Bob: Battle for Azeroth had a stupid and contrived war, and I’m glad the Alliance and Horde are at better terms now. Not everything has to be continent-wrecking. Dragonflight had a massive landmass to explore, with plenty of local lore and sidequests fleshing out the cultures.

This isn’t really an argument about the quality of these two expansions, but rather about personal preferences for the types of stories Alice and Bob like being told in the Warcraft setting. For some people, Battle for Azeroth and Dragonflight were their Warcraft, and for others, they weren’t Warcraft at all. It might be no coincidence, then, that the most well-received and nostalgic installments — Warcraft 3, Wrath of the Lich King, Mists of Pandaria, and Legion — catered to all three pillars.

Comic Book Heroic Fantasy

Warcraft has a very distinct visual style. It is instantly recognizable, setting the franchise apart from both “gritty” generic fantasy and cacophony-of-color mobile games. Somehow, when playing Warcraft 3, we regard the low-polygon in-game models and the highly detailed and realistic cinematics as sharing the same DNA.

Some call Warcraft’s graphics cartoony. I beg to differ. The Mario games have cartoony graphics. So does Animal Crossing and to a lesser extent Team Fortress 2. Warcraft 1 and 2 had cartoony visuals, evoking illustrations for a children’s fairy tale book, but from Warcraft 3 onwards, the art direction has been and remains consistent.

To once again quote art director Samwise Didier:

The art we created completely separated us from other companies’ art styles. Where most companies were pushing realism and realistic characters, we opted for a comic book version of fantasy. We didn’t want to be Lord of the Rings or standard D&D fantasy. We wanted our characters to be the superhero versions of fantasy characters, rock stars with battle axes, with each one of our heroes and units looking like they could take on a whole army by themselves.

The visual style of Warcraft 3 was inspired by comic books. While comic books come in many genres and have historically had many different visual styles, the most iconic comic books — the things we think of when we say “comic books” — are Marvel and DC superhero comics, with their vivid colors, exaggerated physical features like muscles and costumes, and absurdly on-the-nose character names.

…Okay, that last one is not a visual feature. Still, it accurately describes Warcraft as well. Warcraft 3 was a collaborative effort, an effort that led to essentially the creation of a comic book in video game form when Samwise Didier’s understanding of how comic books are drawn was married to Chris Metzen’s understanding of how comic books are written.

Comic books are a serialized medium. A reader can see a comic book on the stand, get attracted to the bright evocative cover, and read the issue without necessarily having the preceding ones. A comic book issue needs to stand on its own well enough that people who don’t have previous issues can still quickly get up to speed and understand the gist (even if the subtleties might be lost to them), and an issue has to not only tell a solid story on its own, but, if it’s part of an ongoing story arc, it has to also advance the overarching plot.4

Individual Warcraft games not only are evocative of comic books in their visual style, but they’re similarly structured narratively. To understand the plot of a Final Fantasy XIV expansion, you need to play through all previous ones, from the very beginning, because they continue lots of references to prior events and characterization; because of this, playing through FFXIV feels like reading a series of novels with an overarching plot and a single core cast. In World of Warcraft, on the other hand, each expansion is largely self-contained, built around a central theme like “undead in the frozen north” or “martial arts in fantasy China”. The stories are also mostly self-contained and easy to understand, and plot links between expansions can be explained in one or two sentences each (“the deposed warchief escaped to an alternate universe Draenor and convinced its orcs to invade Azeroth”).

Like archetypal comic books, the Warcraft setting is accessible. Though modern Warcraft lore is expansive and contains dozens of distinct cultures, the core build-around of the setting is still the same as it was back in Warcraft 3: sword and sorcery fantasy in an aesthetically-Renaissance-at-its-core world populated by multiple humanoid races. This kind of world is immediately understandable to wide swathes of people (through pop cultural osmosis and The Lord of the Rings movies if nothing else) and the game writers are freed from the burden of explaining what elves, dwarves and orcs are, or what common fantasy tropes are associated with each race. In contrast, if I had to explain the FFXIV setting to new people, we’d be there all day.

Not only is the concept of the setting accessible, but so are the storytelling and the lore. There’s a lot of lore to absorb, but it’s mostly extensive rather than intensive. To get people up to speed on what the heck the in-game cultures are up to, a five-minute recap is sufficient. And like archetypal comic books focus on easily understood stories with broad appeal, so is classic Warcraft storytelling simple, but not simplistic; it involves broad archetypes and tried and true tropes, but it’s not patronizing or insulting to the players’ intelligence.

A Kaleidoscope of Races and Cultures

If I had to do an elevator pitch for Warcraft, it would go something like: “It’s a more colorful D&D where the so-called ‘monster’ races are protagonists too. And there are many of them.”

Old-style fantasy was human-centric. Humans were the default, the race with which the authors thought the readers identified themselves5, and everything in the story was seen through their eyes. Even when this wasn’t the case, fantasy protagonists tended to be obvious variations on the human form, like immortal pointy-eared humans, short stocky humans, or even shorter hairfooted humans. Antagonist races, on the other hand, were all what real-life humans would call monstrous or bestial.

Warcraft broke the mold from the very start, with Warcraft 1, even when the orcs were still evil. Both sides — the humans and the orcs — were given equal screen time, and both sides had their recent history fleshed out. The orcs weren’t just a generic monster horde for the humans to fight. We knew where they came from, who led them, and we had the personal opinions of their side’s writer that set her apart from the others as an individual.

And then came Warcraft 3. The orcs became heroes in their own right. They joined their forces with equally noble-savage-y tauren and trolls. We got not one, but two villainous human leaders acting hostile towards non-humans, and defeating Admiral Proudmoore with minimal casualties among Jaina’s allied humans became a defining moment for Thrall’s reformed Horde.

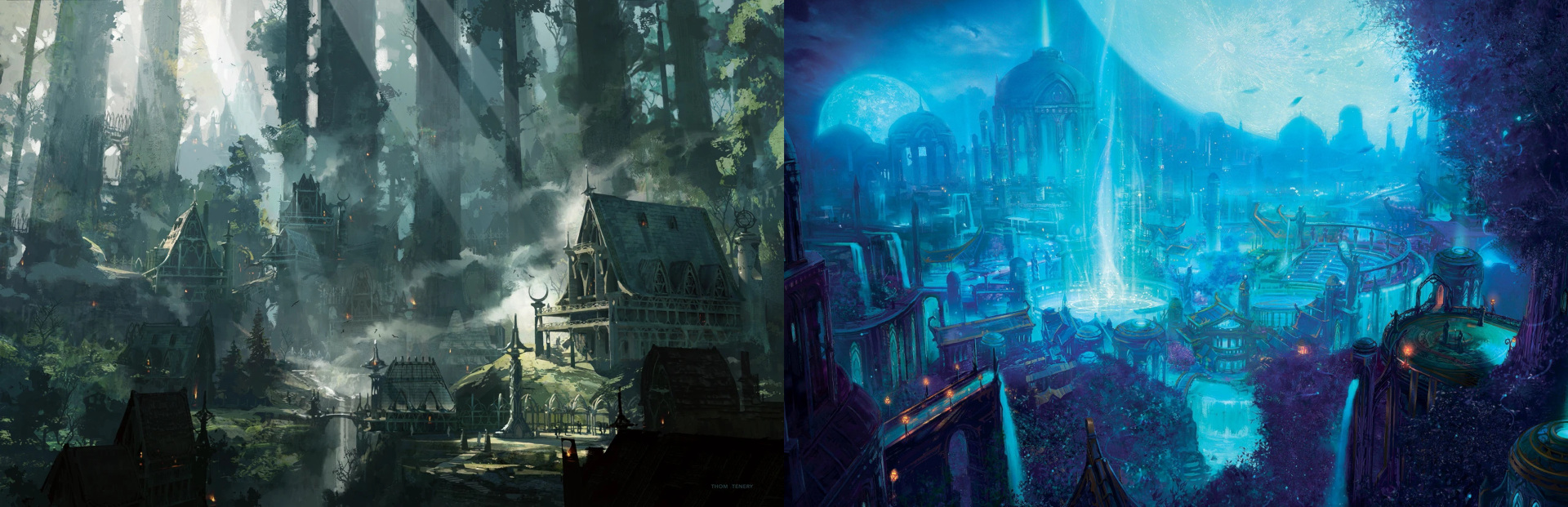

Since then, the number of races in the Warcraft snowballed beyond belief. The thirteen6 races shown on the image above are just the ones that are playable in World of Warcraft from the very start, as of this writing. More races are unlockable. Still more races are not playable, but are nonetheless depicted as cultures in their own right rather than universally evil monsters — and the longer the franchise exists, the more races previously depicted as monstrous get this expanded treatment.

Azeroth is not the Middle Ages or the Renaissance. It might have once been, all the way back in Warcraft 1. Today’s Azeroth is a diverse world filled with just about every fantasy concept imaginable, from tribal warriors and mystics to steampunk inventors to feline centaurs and dragon people to space traders made of living energy. This means that practically everyone can find a favorite race somewhere in the vast lore of Warcraft — and yet, at the same time, newly introduced races are integrated into the existing lore framework, preventing Azeroth from becoming a chaotic and flavorless “anything goes” setting.

A Flavorful, Dynamic World

At the same time, when creating all those races and cultures, the creators of Warcraft didn’t just copy what came before them.

Azeroth isn’t Yet Another Fantasy World. Warcraft 3 borrowed its creatures liberally from D&D, but always put its own unique spin on them. The minotaur-like tauren aren’t despicable monsters living in labyrinths, but noble plains hunters with Native American aesthetics. Satyrs are not merry partying fey creatures, but servants of the Burning Legion, demonically corrupted elves. Gargoyles are not stone creatures adorning gothic castles, but vampiric bat-like creatures allied with the undead. Night elves are not typical fantasy wood elves, but rather a blend of wood elves and dark elves that ended up being recognizably distinct from both. As for Warcraft’s unique take on orcs, I talked about it before.

In fact, Warcraft has put its own flavor on familiar fantasy tropes so consistently that it became notable when it stopped doing this. When Shadowlands introduced its cosmic order regarding the planes of the afterlife, the inspiration from D&D’s Planescape setting was immediately recognizable, and it was telling that they introduced more “classic”, D&D-like satyrs and gargoyles, they had to give them different names because these names were taken by Warcraft’s more original concepts.

Finally, unlike D&D settings, the Warcraft setting is allowed to change. Forgotten Realms adventures written for 5th Edition are supposed to leave the world in the same state that they found it; any would-be evil plots and political upheavals are undone by the end. In contrast, the world of Warcraft can and does change over time. Azeroth during The War Within is a very different place compared to Azeroth in Mists of Pandaria, which, in turn, was politically very different from Azeroth as seen in Warcraft 3. This evolution of the world keeps things fresh, leaves you guessing for what might come next, and keeps the roleplaying scene vibrant.

Hopeful But Not Sanitized

The Forgotten Realms style guide is a guide written by Wizards of the Coast for prospective writers creating stories and adventures for the Forgotten Realms. It is a very interesting document given that it even exists and is public, highlighting how much importance WotC places in having the most popular D&D setting feel consistent in tone. What’s of interest to us now is this tidbit:

The Forgotten Realms is a hopeful setting. The good guys will eventually win. This hopeful tone sets the Forgotten Realms apart from settings like Greyhawk (which is cynical) and Dragonlance (which is a setting of romance and tragedy). While not every moment of a story or image in art should be hopeful (the villains need their time in the spotlight, and bad things do happen), keep this tone in mind.

I think this is equally applicable to Warcraft.

Warcraft is a hopeful setting. Even when things look bleak, the armies of the world are in tatters, kingdoms are burning and civilization is reduced to refugees fleeing across the sea, we know that this won’t last. The good guys will eventually win. Fortresses of evil will fall, dark lords will be overthrown, and the sun will shine bright again. The heroes of Warcraft, like Thrall, Jaina Proudmoore and Uther, embody idealism that is continuously tested by circumstances, but is eventually proven right. Traitors and violent maniacs get their due, and friendship and compassion is what ends up saving the day.

Warcraft can be dark, but it’s never mean, never cynical. This isn’t Game of Thrones. So far, only Shadowlands was dumb enough to mess with this unwritten rule7 by presenting an afterlife so bleak and so soul-crushing (literally and figuratively) that many people considered it horrible in its very conceit as a whole, even leaving aside the villain’s machinations. Shadowlands was also, coincidentally, the worst-received expansion in WoW’s history.

Even when major characters die, it typically happens as a result of their own choices. Muradin died because he kept enabling Arthas despite clear signs of his slide into insanity. Uther died because he stayed to protect a doomed Lordaeron. Grom Hellscream died in repentance for helping the Burning Legion enslave his people. Maiev died (maybe) as she lived, a hasty monomaniac focused on recapturing Illidan with no long-term plan. Garithos died because he was stupid enough to believe Sylvanas’s promises. And Admiral Proudmoore died because he couldn’t let old hatreds go.

At the same time, however, Warcraft isn’t a children’s cartoon.

In a sanitized story, everything is neatly resolved by the end. The bad guys are killed, captured, or abandon their evil ways. They’re stopped before they do too much damage, and what damage they manage to do is repaired. The good guys survive their ordeals, overcome hardships and heal completely from their scars, physical and mental, just in time for everyone to hold hands and sing kumbaya.

Warcraft is not that.

Bad things happen to good people. Sometimes undeservedly bad things happen to the best people. Thrones are toppled, ruined kingdoms stay ruined, and defiled lands stay defiled instead of being instantly restored by magic. It’s possible to bounce back, but it takes immense effort and many years of labor. Even on a personal scale, even the most worthy people are not pure paragons of virtue, but are mere people, afflicted by flaws like pride, ignorance, and prejudice. We can see this in how Of Blood and Honor doesn’t end with Uther seeing the error of his ways and acquitting Tirion; no, it ends with Tirion convicted and losing everything, and only his subsequent rescue of Eitrigg — which still leaves him a hermit and an exile — prevents the story from going too bleak, instead giving us a bittersweet ending.

So when a Warcraft story starts going too sugary, and everything is too neatly resolved with everyone becoming friends and having no lasting negative consequences, for some people it’s a welcome respite from constant death and destruction, and for others, it’s not Warcraft at all.

Conclusion

I could go on and on about what “feels like Warcraft” to me. Like weird single-biome environments that put a temperate forest right next to a savanna or a snow plain, or the wildly uneven technology levels with knights and castles right next to steampunk tanks and airplanes, or the sheer dedication to catering to casual and hardcore players alike, or largely modern social mores despite the historical dressing, or… or… or…

I hope, at least, that I’ve at least covered the major points — and I’m interested to hear what you consider part of the feel of Warcraft.

And with that, our exploration of the origins of Warcraft as we know it draws to an end.

We have journeyed through Blizzard’s Experimental Era (Warcraft 1, 2, and Warcraft Adventures) and part of the Classic Era (Warcraft 3 and The Frozen Throne). We have seen the setting evolve through the games, and we have seen novels give it much-needed depth.

Warcraft 3, with its greatly expanded world, formed the skeleton of the setting. It jumped widely from location to location and from character to character, using broad, sweeping characterization. After it, installments that built deep rather than wild fleshed out the world of Azeroth, putting some much-needed meat on these bones. I’m talking, of course, about the tie-in series of D&D supplements, Warcraft: The Roleplaying Game.

…Oh, and World of Warcraft too.

Where Warcraft 3 built wide, giving us new lands, new races and new factions, the RPG and WoW built deep, mostly focusing on fleshing out the material we had in broad strokes. In doing so, they turned Warcraft into a setting with enough detail that roleplayers, myself included, could create and play out our own stories in the world that Blizzard built.

But that would be a story for another time.

~ End of Volume One ~

-

Four if you count Pandaria, but technically we don’t yet know where it is or whether it’s even a continent. ↩

-

We haven’t met Brann in-game yet, but he’s the younger brother of Magni, the king of Ironforge, and Muradin of human campaign fame. ↩

-

Personally, I’m a fan of the exploration pillar, which explains why I liked Rexxar’s campaign and was excited for Mists of Pandaria and Dragonflight. ↩

-

I haven’t read many comic books, so take this with a grain of salt. ↩

-

And considering the amount of apologism for obviously villainous human factions like the RDA Corporation in James Cameron’s Avatar, “humanity, right or wrong” is indeed, unfortunately, the worldview of at least some sci-fi and fantasy fans. ↩

-

There are fourteen images, but two of them depict the same race, highlighting that it’s available to both the Alliance and the Horde. ↩

-

By all appearances, unintentionally. The Shadowlands are horrific by writer ineptitude, not by design. ↩

Leave a Comment