Warcraft Retrospective 27: Beneath the Stars of Ever-Eve

And so we get to the final campaign of Reign of Chaos: the night elf one. And… oh boy, it’s going to be awkward for me to talk about it.

It’s no secret that I like night elves. This website is, after all, named after a night elf roleplay character of mine. It’s furthermore no secret that I like elves as a fantasy concept. It might, however, surprise people who know me as the Argent Dawn realm forum’s resident elf-lover that I’m really not that fond of the elf concept in general, except for two races in all of fantasy that I know of. Most varieties of elves that have been invented by fantasy writers over the past few decades — at least those that are actually called elves1 — leave me either annoyed or indifferent, except for exactly two of them: Tolkien elves, and night elves.

Before you raise your pitchforks (or bows), let me say a few words in my defense.

An Abridged, Oversimplified, and Highly Inaccurate History of Elves

In the beginning, there was Germanic folklore and mythology. I’m not actually qualified to talk about it, and at any rate, any cursory overview of a folkloric concept will inevitably involve simplifications and generalizations. Premodern conceptions of elves have apparently ranged from diminutive to human-sized; they have at various times been conflated with fairies or used as am umbrella term for mythological beings that included forest spirits, dwarves, and even trolls; and then there’s Norse mythology with its [distinctions] between light elves (Ljósálfar), dark elves (Dökkálfar) and black elves (Svartálfar), the latter two of which may have been the same or different, or they may have been dwarves, or distinct from them. It’s a bit of a mess.

What’s important for our purposes is what I’ve already mentioned before when talking about orcs: mythological beings were conceptualized as an Other defined primarily by their interactions with humans, part of the wild, unknown world beyond the safety of civilization. Elves could help or hinder humans; they could charm human onlookers, or bring diseases upon the townsfolk, or kidnap human children and replace them with changelings, but at any rate they were them, they were other, and storytellers’ audiences weren’t asked to put themselves in their shoes.

From Elizabethan times onwards, thanks to Shakespeare, the words “elf” and “fairy” ended up being used somewhat interchangeably for diminutive beings, an image that by Victorian times got codified as tiny human-like beings with butterfly wings and often pointy ears. In modern D&D terminology, we’d call them pixies. This was the image that Tolkien’s contemporaries in the early-mid 20th century tended to associate with the word “elf”, much to his annoyance.

And then, taking inspiration from Germanic mythology, Tolkien wrote his elves, forever changing the associations of the word and in effect creating a whole new archetype.

The Sundering of Tolkien Elves

Tolkien drew from a variety of mutually contradictory inspirations, including the aforementioned Norse Ljósálfar and Dökkálfar and Irish Tuatha Dé Danann, and synthesized them with original elements of his own, suggested in part by his own Catholic religion. The end result was different in many ways from both his mythological inspirations and the armada of imitators that followed, and is far beyond the scope of this blog; I’ll focus on the details that matter for the discussion of Warcraft.

In Tolkien’s world, elves are a race of beings much like humans, but taller, more conventionally beautiful2, stronger and wiser, immune to aging and sickness and thus capable of living forever, barring accidents, and capable of superior craftsmanship honed over their long lives to such an extent that it resembled magic. The first elves were created directly by the one supreme god before the Sun and the Moon existed, so the first thing they saw when they awakened were the stars, which they’ve come to love forever after.

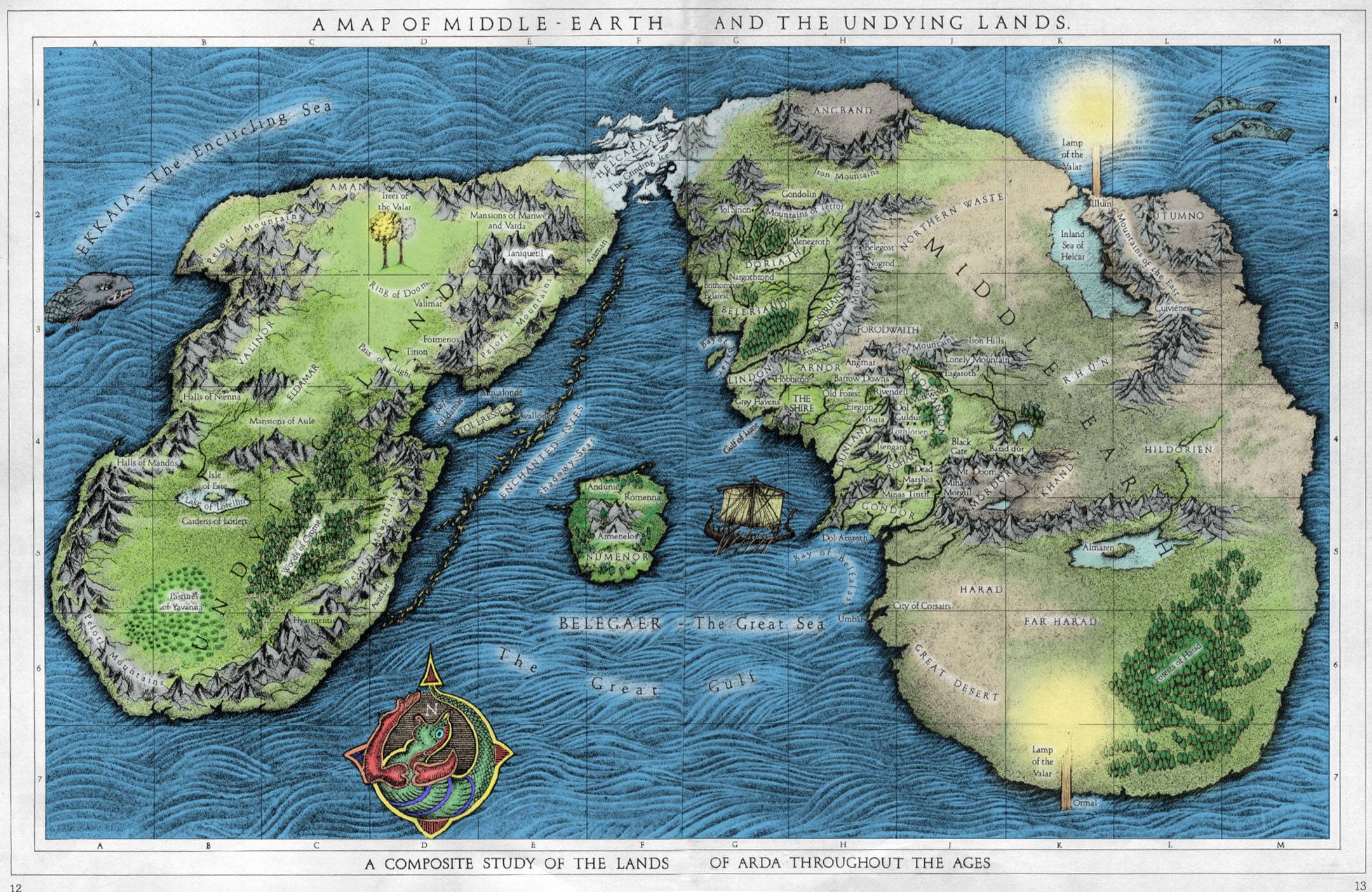

Prior to that, the “pagan gods” or, if you will, demiurges of the world, creators of the land, sea and wildlife, had a series of fierce battles with their fallen brother, the Satanic arch-villain of the entire setting, during which their original design for the world — a single continent with a great lake in is center — was broken into two continents with the Great Sea between them. Forsaking the eastern continent — known in later times as Middle-earth — to the Enemy to do as he pleased, the gods retreated to the western continent, where they built their earthly paradise known as Valinor.

After the elves awakened, the gods invited them over the sea to dwell with them in that western paradise, and that caused a divide among the elves. Some refused outright. Those who agreed to travel west came to call themselves Eldar, or “people of the stars”. Those were in turn split into three nations even during the journey, and then some of them stayed behind in Middle-earth, never completing the journey to Valinor. And of those Eldar who did reach Valinor, due to a complicated series of events, a faction later returned to Middle-earth and were, for a while, forbidden by the gods to come back to Valinor. These exiles founded kingdoms of their own, passing much of their knowledge to the humans of Middle-earth.

Tolkien was a linguist, and a major motivation for worldbuilding, for him, was constructing a world that his invented languages could exist in. For this reason, the geographical history of his world was dictated in part by linguistic considerations. Originally, all elves spoke one language3, which, though millennia of separation between elven peoples and nations, split into Quenya in Valinor and Sindarin in Middle-earth4; the Great Sea, as a natural geographical barrier, is thus an in-universe justification for the existence of two languages, as well as divergent cultures.

That last point bears elaborating. Tolkien elves are not a single racial monoculture; it would be highly inaccurate to say that they all live in forests and practice archery. But they’re also not divided into distinct species, like Warcraft’s night elves and high elves or Forgotten Realms’ sun elves, drow, and sea elves. Like real-life humans, they’re all biologically the same species divided into nations, each with its own distinct culture. Some indeed live in forests and are renowned for their woodland archers, others live by the shore and are famous for their sailors and shipwrights, and others still live in magnificent cities and have produced great artisans and scholars.

The race as a whole, as such, defies easy generalization — in my opinion, at least. Tolkien elves are individuals and display a variety of personality traits, virtues, and flaws, even within a single culture. Some are regal and thoughtful while others are playful and whimsical; some are open-minded and compassionate while others are xenophobic and quick to anger; and so on and so forth. If I were to name some general traits, I’d say that Tolkien elves are slow to change and to adapt to change, and are largely content for the world to remain undisturbed; they don’t seek to break or dominate the wills of others; and while some elves throughout history fell to hubris and selfishness and committed atrocities like mass murder, genocide, and rape, very few have ever willingly served Evil as a cosmic force.

Mind you, all this is known from Tolkien’s posthumously published prequel book, The Silmarillion, which is Elvish for “Warcraft Chronicles of Westeros”. By the time of The Lord of the Rings, the few elves still left in Middle-earth are a remnant of a remnant, and the reason they come off as such goodies-two-shoes is because everyone more impatient, reckless, or malicious has long either died or sailed away. The remaining ones are world-weary, having lived for many millennia in a fading and decaying world while they themselves stayed unchanging. They’re associated with twilight, while daytime is the domain of humans, the younger race, and of all the gods they most revere Elbereth, the Queen of the Stars, who is associated with the night sky and with hope in the deepest darkness.

Now, the reason I’m bothering to say all this is because I listed specifically the facts that are going to be relevant to Warcraft, going forward, and we’ll soon see the thematic parallels. I’m also, once again, trying to show that Tolkien put a lot more nuance and thought into his world than might be evident at first sight, and avoided many of the pitfalls of fantasy writers who came after him. He drew from many sources and, in turn, left his successors many themes to draw from in turn. More than that, by making his elves protagonists and viewpoint characters, and by creating in-universe writings from their perspective, he let us see the world through their eyes. In Tolkien’s world, nonhumans like elves, dwarves and hobbits are not Other, but people with rich inner worlds of their own.

…And then of course, most later writers disregarded this worldbuilding and remembered Legolas, so he became the default template for the ISO Standard Fantasy Elf going forward.

After Tolkien

As we know, The Lord of the Rings was so popular that Tolkien’s conception of elves thoroughly displaced everything that came before it in the public consciousness. But all too often, later writers fell into shallow stereotypes.

From my experience, post-Tolkien elves tend to fall into two broad categories. On one hand we have writers whose elves or thinly-veiled elf-stand-ins are unrealistically perfect, live in a Mary Suetopia, and conspicuously share the author’s exact real-life views on social issues, or at least views the author approves of. They can be devoutly religious, or they can be atheists and vegetarians; prudish or sexually liberated; or outright ecoterrorists if the author wants to preach environmentalism. In any case, we’re supposed to find them sympathetic.

The other kind of annoying elves lean not on moralizing, but on the power fantasy aspect. These elves are better than you at everything, dear reader, and they want you to know it. They’re stronger than you, faster than you, smarter than you, prettier than you, and better than you at any setting-relevant skill you can name. It comes off as smug and condescending, and at times strays uncomfortably close to a Master Race eugenics fantasy. Bonus points if they act like entitled human teenagers with none of the supposed wisdom that their unfathomably high age is supposed to bring.

And then there’s D&D, as its own thing. As a roleplaying game or, rather, a toolkit for hosting roleplaying games, it’s not really about anything; it brings you the building blocks, but the adventure author is supposed to assemble them into a game that hopefully weaves a story about something. At first, Gary Gygax, who is given way more credit for his part in creating D&D than he deserves, favored humans over nonhumans and believed D&D should have been about humans first and foremost; originally “elf” was both a race and a class, so you could be a human fighter, or a human cleric, or… an elf, period. And then D&D went overboard and started adding new elf varieties for each environment you can think of — as actual biologically different races, each with its own shade of technicolor skin color. And so now we have sun elves, moon elves, star elves, wood elves, wild elves, grey elves, sea elves, winged elves, and can this madness please stop before, of all the elf cliches, some video game developer copies this one?

…Oops, too late.

And that wasn’t enough. Of all of D&D’s multicolored varieties of elves, one managed to take off to the point of inspiring imitators of its own: the drow, created by — who else? — the notorious misogynist, biological determinist and lover of the concept of evil races, Gary Gygax. As one of the monster races that players are supposed to have no moral qualms indiscriminately killing, drow, also called dark elves, are a universally dark-skinned and near-universally evil race that lives underground and has a fashion sense that I can most charitably describe as “not even disguising the author’s fetish”.

It’s telling that when one Warcraft 3 developer suggested making “dark elves” a playable faction (which ultimately led to the creation of night elves), none of them wanted to go with drow.

Enter Warcraft

Warcraft 2 made a big jump from faux-Christian humans against hellish orcs — as seen in Warcraft 1 — to a more typical roster of fantasy races, introducing elves, dwarves and gnomes for the Alliance, and trolls, ogres and goblins for the Horde. Traditional adventurer races versus traditional monster races. It made sense.

It seems to me, however, that nobody was interested in actually fleshing out Quel’Thalas. The logic was, it seems, that since they were going for a high fantasy setting, it needed elves in the same way that Superman needs those little red underpants outside his costume: which is to say, not at all, but they’re always there anyway. I mean, pretty much the only things we knew about Quel’Thalas prior to Warcraft 3 were that they had archers and druids (the latter of whom are conspicuously absent in Warcraft 3), provided the Alliance with destroyer ships and lumber mills, and had a history of enmity with the trolls. In Warcraft 2, they weren’t yet known as “high elves”, just “elves”, with no reason to believe that there were more kinds of them. And then, throughout all the Warcraft media until and counting Reign of Chaos, we got exactly three named characters from Quel’Thalas: Alleria, Vereesa, and Sylvanas. And they — what a coincidence! — were all rangers, and at that point, pretty much interchangeable.

And then, with Warcraft 3, came the night elves.

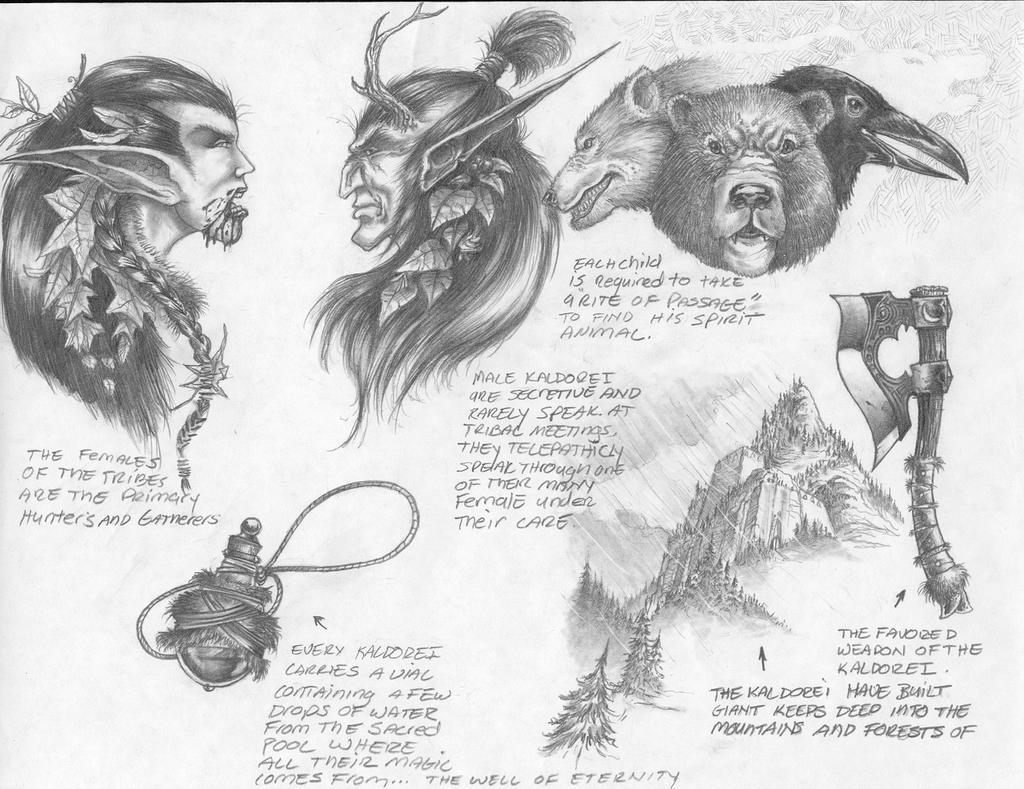

With them came a lot of lore (by RTS standards) that wasn’t, strictly speaking, necessary, but was there anyway — a sign that the worldbuilders were enjoying their work. They have unique and consistent aesthetics that aren’t borrowed from ISO Standard Fantasy Elves, but aren’t imported wholesale from a single real-life culture either, instead borrowing from a variety of real-life cultures and mixing them into something new and fresh. They weave in some of the Tolkienian themes mentioned earlier in a way that shows understanding, not just mindless imitation. And in-game, it all works together: the lore, the visuals, the music, and the characters.

Night elves are very popular to this day and are still one of the most lore-rich races in the setting, which makes it hard to believe that their creation was basically a happy accident.

When brainstorming playable factions for Warcraft 3, the developers debated whether to make elves and dwarves their own factions. There was no majority agreement on making “traditional” elves a standalone faction until someone suggested dark elves. Since they didn’t want to do D&D drow either, they combined “the best of wood elves and dark elves” into a single race. Despite the developers not going with drow, night elves had more drow influences early on than were retained in the finished game, for example, riding giant insects; in Warcraft 3 as we know it, the only elements that survive are dark skin and strict gender roles with a matriarchal bent.

As for their history, as outlined in the manual, I can’t help but wonder if one of the Warcraft 3 writers was a fan of The Silmarillion.

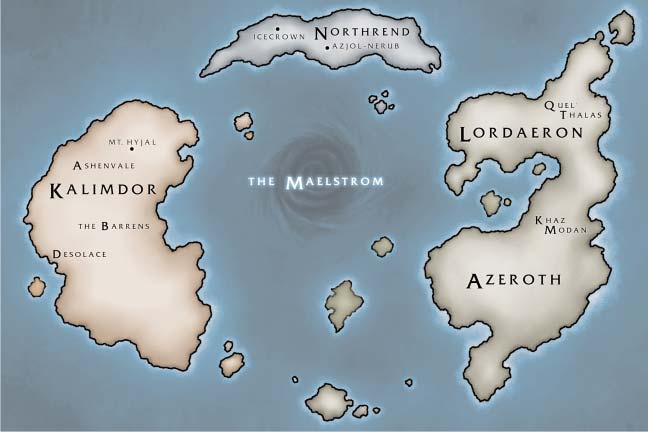

The Titans, the godlike “orderers” of the land, sea and wildlife, were betrayed by their fallen brother, the Satanic arch-villain of the entire setting, who was ultimately responsible for breaking their original design for the world — a single continent with a great lake in is center — into two major continents with the Great Sea between them. Forsaking the eastern continent, the night elves — who called themselves kaldorei, or “children of the stars” — retreated to the western continent, Kalimdor. There they dwell, until mariners from across the sea will come to enlist their help in saving the world.

The night elves once had a glorious civilization, but it was destroyed in the Sundering. Those who remain now are world-weary, having lived for many millennia in a fading and decaying world while they themselves stayed unchanging. They’re associated with twilight, while daytime is the domain of the younger races, and of all the gods they most revere Elune, Mother Moon, who is associated with the night sky and with hope in the deepest darkness.

It’s not a perfect match, and a lot of it could be just coincidence, convergent evolution, or ideas floating in the air. But I really do wonder.

Eternity’s End

And so we get to the night elf campaign, “Eternity’s End”. It’s a rather ominous title — after all, isn’t an eternity by definition endless? I wonder what can possibly–

…Wait a minute, what is that archer wearing? Or rather, why is she wearing so little?

Over my years of roleplay, I’ve heard plenty of in-character excuses for Sentinel “armor”, and none of them really satisfy me. It’s for mobility. Night elves don’t have prudish Western decency mores. Sentinel archers rely on being hidden, so if they’re caught in melee they’re screwed anyway, armor or no armor. And so on and so forth.

Thing is, these are Thermian arguments. Warcraft 3 is not a historical documentary, it’s a mass market video game taking place in a make-believe world. None of these justifications explain the massive shoulderpads and gloves that protect the archer’s shoulders and forearms and nothing else.

Since it’s a 2002 game, I really don’t think any thought process involved in this design went deeper than “Dude, look at the cleavage on that hot chick! 10/10 would totally bang.”

You can’t even claim that it’s specifically a night elven cultural trait that visually distinguishes them from the other races. Here are Jaina and Sylvanas’s in-game models.

Why do so many women in this game like to show off their cleavage on the battlefield?

You want to portray athletic and assertive women, that’s fine. Good, even! Make them wear something sensible that still signals these traits. In a modern setting, in everyday life, a tank top would be appropriate. On a fantasy battlefield… some kind of sleeveless leather vest, maybe. Whatever. I’m not an armor expert. In-universe, I’m sure that a culture with ten thousand years of experience in armorcraft would come up with something that both doesn’t restrict the wearer’s movements and provides actual protection.

Moving on. Let’s dive into the campaign.

Enemies at the Gate

The camera slooooowly zooms in on Tyrande standing atop a cliff. The sky is an ominous shade of orange.

We see her from the front. She’s riding some kind of white tiger. A named archer comes to check up on her.

Tyrande is sensing something dark stirring within the forest. Perhaps the greenskins who killed Cenarius, perhaps something more. She sends an owl scout to look for troublemakers. Turns out humans and orcs are working together chopping wood for construction. It’s an uneasy alliance, but their commander, a paladin named Duke Lionheart, is defusing tensions for the time being.

Warcraft 3 likes to introduce gameplay abilities through cutscenes, which I appreciate, and this mission is no exception. By seeing Tyrande summon and use an Owl Scout in a cutscene, players will have a better understanding of how the ability works. (It’s an invulnerable owl, immune to spells, that you can control to fly around and scout the map.)

Story-wise, however, I already have some questions.

Everyone here acts like they’ve learned nothing from Grom’s disastrous foray into Ashenvale. Presumably, if not Grom himself, then at least some of his warriors would tell Thrall and Jaina that the woods are inhabited, and they’d attempt to parley with the night elves or at least find other sources of lumber to avoid their wrath. Here, it looks like the humans and orcs don’t even know about them.

Tyrande resolves to establish a base and deal with these outlanders as they deserve.

I have to say, Tyrande’s voice fits the character perfectly. It’s fitting for an elven veteran leader who has Seen Some Things over her long life, sounding assertive and world-weary at the same time.

Once the cutscene ends, you gain control of Tyrande and Shandris, except the in-game unit called Shandris in the cutscene actually turns out to be a generic archer no different from any of the others.

Night elves have a rather unique gameplay, with important differences from the other factions. Most of their buildings, including the primary one, are ents treants sentient walking trees that act as units when uprooted (and can attack) and as buildings when rooted. Before a night elf player can harvest gold, the main tree must entangle it with its roots, which takes time. As another antepiece, the player in this mission is asked to manually root the tree of life and entangle the gold mine, so they can learn they can do that.

The worker unit of the night elf faction is the wisp, which looks like a ball of light. According to the manual, legends say that wisps are actually the disembodied spirits of the night elves themselves, but these rumors have yet to be proven. In addition to their role as worker units, they have some minor combat utility: their Detonate ability sacrifices the wisp to drain some mana from nearby spellcasters and deal damage to summoned creatures.5

Unlike other factions’ worker units, wisps harvest lumber without destroying trees and without making trips back and forth; they just circle a tree and give you +5 lumber every 8 seconds. This means that night elves don’t need a lumber mill building to shorten the trips (and indeed they don’t have one), that they don’t have the tactical disadvantage of leaving their base more and more exposed as its surroundings are deforested, and that there’s never any disadvantage of sending all your idle wisps to gather lumber, so you might as well do that.

While waiting for the base to build, we explore its surroundings. Just outside, there’s a tribe of furbolgs that is preparing to move out because of a seeping corruption in the forest, but the shaman wants to rally the rest of his people first. Tyrande agrees to help.

It’s worth putting the main quest on hold and completing this side quest first, as the furbolgs are scattered all over the map, and the enemy won’t start attacking until you establish your base and train five archers. So I trained four archers, picked up some free ones northeast of my base, and went out exploring, finding the furbolgs and destroying their homes once they leave.

Along the way, we fight some Alliance and Horde outposts and disrupt their logging operations. Some of the orcs have captured furbolgs in nets, so it’s not like they’re entirely innocent here.

While this is a simple mission, its lack of pressure lets you assess the strengths and weaknesses of your initial unit, the archer. Archers are the only combat unit we can build in this mission, and while they’re cheap, they’re also really fragile.6 Destroying buildings with ranged units alone also takes forever in Warcraft 3, because the piercing attack type deals the lowest damage to buildings out of all attack types in the game.

Because of this, gameplay mechanics alone encourage you to strike at night. All female night elves in-game7 have the Shadowmeld ability that makes them invisible at night as long as they don’t move or act, and it can be activated on purpose, which makes the unit invisible and untargetable and drops enemy aggro. Therefore, if you’re fighting at night and an archer gets heavily wounded, you can simply hide her, forcing the enemy to switch their attacks to other units.

Once we find all the furbolgs and return to the village, the shaman rewards us with three furbolg frontliners, providing us with much-needed melee support for the archers. Now is the time to train the fifth archer, which completes the main quest and activates a new one: to kill Duke Lionheart, the paladin in charge of the joint Alliance-Horde base.

The base is protected by a mix of human and orc units, and the paladin is level 6, so it’s best to lure him away, and if his troops come with him, he’ll resurrect some of them once. Once he dies, the mission ends.8

But… at that very moment, all hell breaks loose.

At last, the Burning Legion has begun its full-scale invasion of Kalimdor. I like how, once again, they’ve waited for the denizens of the world to thin each other’s numbers, biding their time until one of the sides was decapitated, and only then launched their attack. It shows that they’re smart, patient, strategizing. It sets them apart from generic mindless monster hordes that seek to overwhelm the enemy with sheer numbers. And it builds on what came before, with the Burning Legion using the orcs and undead for their proxy war before entering the world themselves. Thematic consistency!

Sadly, it’s about to be undermined by the next mission, where the demons are made to look like complete fools.

Daughters of the Moon

Tyrande and her Sentinels are on the run from the undead and demons…

…Aaaaand this was where I hit the inventory bug again.

In version 1.31, at the beginning of this mission, Tyrande loses her inventory slots, like Grom did in his second mission, dropping her items on the ground at the start of the intro cutscene. My patience was finally exhausted, so I downgraded to version 1.30, in which this mission played without any bugs and the only thing I lost was the 64-bit build of the game; 1.30 and earlier only have a 32-bit variant.

Archimonde, Tichondrius, and their doomguards chase the Sentinels to a precipice. They kill the archers, and then… one of the most unintentionally hilarious scenes in the entire game happens.

Tyrande, having recognized Archimonde from ten thousand years ago, shadowmelds. (There’s no way that’s her shadow on the ground, right? Must be cast by a tree or something.) Like a Saturday morning cartoon villain, Archimonde kills one of the doomguards on the spot for letting her get away. The unfathomably powerful eredar warlock who leveled a city with a wave of his hand apparently doesn’t have any magical means of seeing through invisibility, nor does he know that Shadowmeld has the crippling weakness of requiring the user to stand still, so Tyrande is clearly still there; nor can any of the demons smell her or hear her breath.

The demons leave, and Tyrande reappears, once again apparently talking to herself.

I love and hate this mission at the same time.

I love it because it’s a genuine stealth mission, a rarity in RTS games. At the beginning, you control Tyrande alone, in an area heavily patrolled by doom guards. She can’t take them solo, even one by one, so she has to rely on Shadowmeld to slip away.

I hate it because this mission runs on game logic.

The mission’s premise relies on enemies dropping aggro and resuming their patrols whenever you hit the magic I key to Hide. This reduces the Burning Legion, a millennia-old demon army that has scoured countless worlds of all life, to total oafs with the attention span of a TikTok addict. Breaking line of sight with Tyrande as soon as she disappears is bad enough, but if Tyrande stands in the way of a demon’s patrol route, it will physically bump into her, walk around, and continue on its merry way like nothing happened.

When people say “this game is too videogame-y”, this is the kind of stuff they mean. Like Shamus Young aptly noted, they’re saying that it too obviously suffers from the limitations of the medium and that the writers have done a bad job at concealing those limitations — either perverting an otherwise serious story to accommodate silly gameplay tropes, or treating gameplay abstractions as literally true.

Anyway, Tyrande continues south, evading the stupid, incompetent, and disappoining minions and snagging some nice loot from under their noses. Eventually she reaches a human footman making camp in a corner of the woods that’s seemingly calm… until five archers appear out of nowhere and ambush him.

This reminds the player, in case they haven’t noticed, that archers can also hide at night.

As the Sentinels advance, Tyrande notices more footmen fighting ghouls. This could have clued her in that they could be useful allies, but her prejudice and rashness are too strong.

A little farther along the road is a small orc outpost fighting undead. While they’re distracted, Tyrande can steal a useful Mantle of Intelligence +3 with the usual “run in, grab item, shadowmeld, run out” method.

And farther ahead still are huntresses, who join us as well. They’re close-range light cavalry riding black panther-like creatures. Finally we get fairly durable frontliner units that archers can hide behind. A huntress can also plant a sentinel owl over one tree, which reveals a small area of the map around it and can only be removed by destroying the tree.

Actually, here’s something that bugs me. What language are the non-Elvish words spoken in?

Mass market fantasy usually handwaves the question of language barriers unless the plot relies on it (like Thrall not knowing Orcish for most of Lord of the Clans). Somehow, people from different isolated cultures, even different continents, can understand each other right away, and nobody draws attention to it in-story. It’s just one of a myriad “I won’t bring it up if you don’t” unspoken agreements between the writer and the audience, and there’s usually an implicit understanding that whatever language the characters are “really” speaking in-universe is rendered as the language of the work (English or otherwise) for the audience’s benefit.

And Warcraft 3 handwaves away the language barrier while also drawing attention to the idea that the characters have different native languages. Night elves talk to each other in a mixture of English and their own language, and Thrall says things like “Lok’tar, my warriors!” with only orcs present. It’s the fantasy equivalent of a character saying “Guten tag, my name is Klaus” in an English-language work, in a scene that takes place in Berlin and there are only German speakers present.

Whatever. Our army keeps growing, and now we have a choice of stealthing past enemies or fighting them head on. Eventually we come across some ballistas, as well as an Easter egg hidden behind the trees.

If we destroy the trees with ballistas (how unelflike of us) and approach this neutral hydralisk with Tyrande, it will join our forces. Depending on your choice, this leads to either an exciting climax or an underwhelming, but practical anticlimax.

Our goal is to reach the teal night elf base in the southeast, but there’s a large undead base in the way. It looks like we’re headed for a siege, and the hydralisk’s really powerful attack would be of great help here… or we can just destroy a few more trees and take the hidden path around the undead base, skipping the final fight entirely. And strangely for Warcraft 3, which usually rewards completing objectives the hard way with more loot, destroying the undead base here yields exactly two rewards: jack and squat.

So I didn’t bother. I ran through the side path straight to the victory cutscene, where Tyrande meets… Shandris?

How is this possible? In the previous mission, Shandris was with Tyrande, then she turned into a generic archer who I’m pretty sure died in my playthrough. Here, she’s not only at a different base that had no contact with Tyrande until now, but she has her own model (or well, a recolor of Sylvanas’s model, but you know what I mean). Was the archer in the first mission originally supposed to be just that, some random archer, instead of Shandris?

Tyrande tells her that the undead who attacked this village were sent by the Burning Legion. Against such might, the Sentinels have only one option: to awaken the druids.

The Awakening of Stormrage

Adding to the mystery of the duplicate Shandris, in this mission she’s nowhere to be found, despite departing with Tyrande at the end of the last mission. Tyrande is talking to an unnamed archer.

The Horn of Cenarius can awaken the druids, but of course, nothing is ever simple. First of all, an orc base is blocking the way to the shrine where the horn is kept. Worse yet, the undead are advancing on the nearby barrow dens, where Furion Stormrage, the wisest and most powerful of all the druids, lies in his slumber. For now, the dens are protected by trees, but if the undead chop through them all, the player will lose.

This mission is fairly easy on normal difficulty and, reportedly, frustratingly hard on hard, owing to the small margin of error because the undead clear the trees faster on hard. On normal difficulty, you can just build a large army and pulverize the orcs. On hard, you might have to run through the orc base, likely taking some losses but hopefully keeping enough of your force intact to face the real obstacle here, which is the primal guardians protecting the Horn of Cenarius. They look like colorful ghostly Cenariuses (Cenarii?) and are supposed to use powers of fire, frost, and lightning.

And indeed, at release, that was what they did. These elemental powers are given to them by their Orbs of Fire, Frost, and Lightning, which they’re supposed to keep in their inventories. Here, in the less-bugged-than-1.31-but-apparently-still-bugged version 1.30, they dropped their orbs on the ground, and I was able to actually pick them up.

Even without their orbs, the Primal Guardians are no slouches.9 They’re strong spellcasters and have entourages of owlbears with them. To even the odds a bit, in this mission we unlock dryads, daughters of Cenarius, who are immune to spells and magic attacks and can dispel magic on autocast, making them the most convenient counter to enemy buffs and debuffs like Bloodlust and Slow. They also have really sweet and cheerful unit quotes.

Once the Primal Guardians are down, Tyrande sounds the Horn of Cenarius, and Furion awakens.

He immediately shows us how powerful he is by animating the entire grove between him and the undead base, making quick work of them.

And that’s it. A short and sweet mission before the absolute marathon of the following one.

Next up: the finale of Reign of Chaos, where allies expected and unexpected enter the scene, and a tree explodes!

Illustrations:

- Ängsälvor (Swedish “Meadow Elves”) by Nils Blommér (1850), public domain

- Illustration of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream by Arthur Rackham, public domain

- “Ossë and the Teleri”, by Steamey

- “A map of Middle-earth and the Undying Lands”, from David Day’s A Tolkien Bestiary

- D&D elves by Todd Lockwood, from the book Forgotten Realms Campaign Setting 3rd edition

-

There are some thematically elf-adjacent races that I do like, but they’re neither called elves nor look like stereotypical fantasy elves. ↩

-

And Tolkien probably didn’t picture them with pointy ears; at the very least, this detail is never mentioned in his stories and appears to be a later fan conflation with Victorian elves and fairies. There’s also a textual instance of a human disguising herself as an elf in a traveling company of actual elves, which would be difficult if the two races could be easily distinguished by ear shape. ↩

-

Which can be thought of as their equivalent of Proto-Indo-European. ↩

-

Plus a few less important ones that Tolkien didn’t develop in detail. ↩

-

Remember this. It will become important very soon. ↩

-

Maybe you’d be more durable if you wore actual armor, you dimwits! ↩

-

The game is very consistent about this. Male night elves don’t have Shadowmeld. Female units that are not night elves (specifically, dryads) don’t have it either. When the expansion added a new female hero, she got Shadowmeld too. And then Reforged added a female skin for the demon hunter hero, increasing diversity at the expense of mechanical consistency. Sigh. ↩

-

Which might not be what you want. There’s a Circlet of Nobility hidden in a tent back at the back of the base. If you want to get it, the best way is probably to sneak in with Shadowmeld, grab it with Tyrande and retreat, and only then amass a force and kill the paladin. ↩

-

Actually, why are we even fighting them? Couldn’t whoever put the horn there tell them to stand down? Same team! ↩

Leave a Comment