Warcraft Retrospective 19: Exodus of the Horde, Part One

All right! Let’s start Warcraft 3: Reign of Chaos, and play through all the campaigns, in order. If you want to see a video review of the campaigns, I recommend this one by GiantCrabGames, which covers both the base game and the Frozen Throne expansion in amazing detail, while also focusing on what makes the Warcraft 3 gameplay captivating.

Before I play Warcraft 3, however, there’s one question to clear up.

Thank you, Elephant in the Room. In January 2020, Blizzard forcibly replaced the original version of Warcraft 3 with a remaster called Warcraft 3: Reforged, whose quality has been… controversial to say the least. Reforged is now the only edition that you can download directly from Battle.net. It has two versions of the campaigns — one nearly identical to the original version1, with old models, and one with revamped models and some mission changes as well, including four completely revamped missions.

For this retrospective, I’m going to use the original edition of Warcraft 3 — specifically, version 1.31, the last version of classic Warcraft 3 before it was overwritten with Reforged. It has all the original graphics and the unchanged campaigns, but also support for widescreen and 4K resolutions.

Starting the Game

Back in 2002, I was the first student in my class to get my hands on Warcraft 3 at release. A local game store had downloaded it over the Internet (which, back then, was either tremendously slow or tremendously expensive), and I gave them a blank CD to burn it on, which I then shared with my friends while they were waiting for physical CD releases to appear in stores. It really is a special feeling to be the first person in your group to get hold of something new — especially something this long anticipated.

I didn’t have any manuals, either online or offline, and wasn’t exposed to any spoilers. I went into the game, and the campaign story, completely blind, and when I launched Warcraft III.exe for the first time, I had absolutely no idea what to expect.

Reign of Chaos starts with a short cinematic where a human and an orc fight, but suddenly a meteor falls on the grass between them and turns into a golem glowing sickly green. Then we see the human and the orc’s severed arms lying in water as lightning strikes. By Warcraft standards that’s pretty disturbing imagery — and it’s perhaps no surprise that it was toned down in the Reforged version of this cinematic.

We know it’s a 2002 game because holy compression artifacts, Batman. Blizzard worked hard to fit its game onto a single 700 megabyte CD (DVD drives were for the rich) in an effort to make it as affordable and widely installable as possible. It looks even blockier on a 4K screen.

The main menu is much more immersive than in previous games, intended to carry the impression of something heavy and physical. When you click a button, the chains lift the panel up, with the sound of chains moving, and a new panel comes down. It ends up feeling really immersive, and Hearthstone will later learn from Warcraft 3’s example.

Single Player. Campaign. Here we go…

There are two difficulty levels: Normal and Hard. There’s also an Easy mode, but it’s only unlocked by failing a mission on Normal difficulty. Reforged makes an easy mode available from the start, only it calls it Story mode. Not being a challenge-oriented player, I’ll play through the campaigns on Normal difficulty.

We click the label for the prologue campaign… and get treated with an absolutely goosebumps-inducing pre-rendered cinematic.

A raven on a lavishly rendered field observes a battle between humans and orcs. There are footmen, grunts, a catapult, and a strange horned riding beast. Then meteors rain from the sky, and a mysterious cloaked man speaks to Thrall.

The sands of time have run out, son of Durotan. The cries of war echo upon the winds. The remnants of the past scar the land, which is besieged once again… by conflict. Heroes arise to challenge fate, and lead their brethren to battle. As mortal armies rush blindly towards their doom… the Burning Shadow comes to consume us all. You must rally the Horde and lead your people to their destiny!

In his hut, Thrall awakens in shock.

Chasing Visions

Thrall rides out, dressed in his black armor, wielding the Doomhammer and riding a… black wolf? In Lord of the Clans, he bonded with a white wolf, and the generic Far Seer hero rides a white wolf too, so I don’t know why they made this change.2 A mysterious raven, subtitled as “The Prophet”3, prompts Thrall to follow him, then flies away.

When we finally gain control of Thrall, a narrator voice begins educating us in the basics of controlling units, and I mean the very basics. Blizzard really tried to make Warcraft 3 have as wide an appeal as possible, so the campaign doesn’t assume you’ve ever played any RTS game before. Reign of Chaos has a very smooth learning curve, slowly increasing the difficulty from mission to mission, and from campaign to campaign, introducing concepts and letting you play with them in a less stressful environment, until the “final exam” last mission of the entire game.

Thrall is a hero unit. Though hero units existed in Warcraft 2, they were just beefed-up and recolored versions of regular units. Warcraft 3 expands the concept far beyond that, to something like a mini-RPG — and these hero units are what a lot of the entire game design is built around. Hero units are far stronger and sturdier than regular units; they gain experience points and levels (with a maximum level of 10), unlock abilities and can carry up to six items. These all persist through missions and even across different campaigns.

In Warcraft 3, Thrall is a Far Seer, a ranged spellcaster. He never actually fights with his hammer in melee — instead, he hurls lightning balls at enemies. He starts with the Far Sight spell, which reveals a bit of terrain for a few seconds before the fog of war covers it. Personally, I don’t find it that useful in the campaign except for revealing invisible units, but I assume it’s pretty useful in multiplayer.

Guided by the narrator, we proceed through the banners, learning about unexplored terrain and the fog of war along the way. Soon, Thrall reaches some orc buildings, where three grunts join him.

Here we start seeing what makes the Warcraft 3 campaigns so special: the missions are absolutely full of stuff happening. Warcraft 1 and 2 pitted player bases against each other, but otherwise their missions were just empty terrain. Warcraft 3 introduced very, very versatile scripting capabilities into the engine, and as a result, each mission is full of triggered events that liven up the gameplay. You never know what might be around the corner. Unlike custom mission objectives in Warcraft 2, none of these events are hardcoded: you can open the campaign maps in the really powerful map editor, inspect their scripts, and write your own scripts for custom maps — and boy, did the fandom go wild with custom maps.

These screenshots very much showcase the aesthetic Warcraft 3 pioneered, which became standard for the franchise going forward. Everything is vibrant, colorful, distinct, exaggerated to be instantly recognizable in the middle of frantic RTS gameplay. This was an intentional choice on Blizzard’s part. In the words of art director Samwise Didier:

The art we created completely separated us from other companies’ art styles. Where most companies were pushing realism and realistic characters, we opted for a comic book version of fantasy. We didn’t want to be Lord of the Rings or standard D&D fantasy. We wanted our characters to be the superhero versions of fantasy characters, rock stars with battle axes, with each one of our heroes and units looking like they could take on a whole army by themselves.

Soon, Thrall and the grunts reach and kill a gnoll, then three gnolls (the narrator uses this encounter to teach the attack-move command), and Thrall levels up, learning the Chain Lightning spell. The path crosses a river, where we have our first encounter with one of the long-standing mascots of the Warcraft franchise: fish people called murlocs.

Like I said, the gameplay of Warcraft 3 is centered around hero units leading stacks of regular units. Heroes are supposed to gain experience, and experience is mostly gained from killing enemies. To ease the process, Warcraft 3 has groups of neutral enemies, called creeps, scattered across both campaign and multiplayer maps, often guarding gold mines for base expansion, beneficial map features, or dropping items when killed. To keep things fresh, there’s a lot of different varieties of creeps — enough that you could fill another D&D Monster Manual with the creatures seen in Warcraft 3 alone. Even on this tutorial map, there are no less than five different varieties of creeps, and that doesn’t count your own playable orc units.

One of the murlocs drops a potion of mana. Mana is spent on all clickable (active) hero abilities. Some heroes have one passive ability, which simply provides a continuous benefit and doesn’t need to be manually activated.

When we cross the river and reach the next banner, the night falls.

The day/night cycle is another innovation of Warcraft 3 compared to the first two installments (and Starcraft). Normally, units cannot see as far at night as they can during the day, and organic creep units sleep at night. One of the defining features of the fourth playable race in this game, the night elves, is that, fittingly for their name, they have gameplay features that interact with the day/night cycle.

Here is the first time that we actually get to make some choices. So far, the path we’ve followed has been completely linear. However, from this point on, there are some sidepaths we can explore for bonus experience and loot.

For example, there’s an easy-to-miss side path leading to a forest clearing where a potion of healing is just lying around.

Along with base building and combat micromanagement, exploration is one of the gameplay pillars of Warcraft 3. The maps contain very little unused space; instead they’re filled to the brim with secrets and optional encounters. So far, the Narrator has been hand-holding us across the main quest, but nobody encourages us to step off the beaten path and explore. This is yet another brilliant part of Warcraft 3’s mission design, is that it simply counts on your own curiosity to drive you to these optional areas. You see that the main road is leading you to the mission objective, but there’s also this sidepath leading into the black area — what secrets does it hold? And in these baseless missions where you control a limited stack of units, there’s usually no time pressure, and you can explore the entire map at your leisure.

And that is how you establish — even with a small number of geographically small missions — that the world is large, full of unexplored wilderness, and there are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.

There are three more optional encounters here: a sleeping ogre, whom you can either pass by, or wake him and fight; three stone golems, who don’t sleep at night (and are, annoyingly, immune to Thrall’s Chain Lightning), one of whom drops a Ring of Protection +1; and a camp of sleeping forest trolls, who drop a Manual of Health that permanently increases Thrall’s hit points.

This game was heavily inspired by D&D and its clones, in addition to classic RTS mechanics, and influenced a lot of WoW’s design in turn.

Finally, our little party reaches the Prophet, who has been hovering in raven form all this time, patiently waiting for Thrall to clear the map and gather phat lewt. It’s just the world that is ending, after all. No pressure.

The Prophet laughs at the suggestion of being human, and Thrall senses that “the demons… are returning”. The spirits, conveniently, tell Thrall to trust the stranger, and, having no real reason to say in the human lands and every reason to explore new horizons, he decides to gather the Horde for departure.

I have to note that characters’ reactions to the Prophet in this story are very binary. Either they immediately trust him because of the spirits/a hunch/a dream, or are immediately dismissive and refuse to even entertain the possibility of there being a grain of truth in his words. Nobody really sits down to have a prolonged conversation with him. How does he know all this? Why is Kalimdor so vital to saving the world? Why can’t it be done any other way? Why does he fly around making cryptic messages to leaders instead of trying to spread the word to the people? He pretty much refuses to explain anything and expects people to blindly abandon their homes at his word.

These are good questions to ask, but it’s only something you notice after replaying the game or thinking hard about the story, not something that pulls you out of the story. Which is to say that storytelling problems are a gradient rather than black and white. Warcraft 3’s story is not exactly deep; it’s built around familiar tropes, and the characters are only as developed as they need to be to tell this particular story — that is, they’re pretty flat, but still miles ahead of the first two games. Warcraft 3 storytelling “cheats”, like characters sensing things or immediately trusting each other, are narrative shortcuts meant to tell a coherent story in the RTS format, not something that shatters your suspension of disbelief and yanks you back into the Primary World.

The cutscene writing deserves special praise. The cinematography is basic by modern standards, but back then, in-engine cutscenes smoothly flowing into and out of RTS gameplay were a novel thing. And while the dialogue gets flak for being a cliche storm, personally I think it’s exactly what it should be for this kind of game. It’s memorable, gets the point across, it’s very quotable, and it’s short enough that it never overstays its welcome. Warcraft 3 is very tightly paced; the developers have taken all measures they could to prevent the missions from dragging out, and the cutscenes are just short enough that they don’t bog down the pacing. They also don’t state the obvious and don’t repeat mission objectives verbatim.

As amazing as some fan-made campaigns are, I’ve found out that their dialogue writers can learn from the cutscenes in original Warcraft 3 campaigns, their style, and their purpose: telling a tightly plotted story, not providing long lore dumps.

Departures

Three days later, the Prophet has yet to show himself. Despite his doubts, Thrall continues with the evacuation plan, which now entails building a base camp to house the arriving Horde. A grunt tells him that Grom Hellscream is yet to arrive, which makes Thrall worried.

This mission is a tutorial in base building.

Again, Warcraft 3 sets a new standard in aesthetics, this time it being orc building aesthetics that will carry over into World of Warcraft. There are some changes in how gold mines work. Peons no longer spend time inside gold mines and instead rapidly cycle back and forth, but bring only 10 gold per trip instead of 100. Also, only five peons can gather from the same gold mine efficiently at once. You can assign more, but they’ll spend a lot of time waiting outside.

That building next to the great hall is an Altar of Storms, and its purpose is to raise dead heroes. This design solves a problem with hero units that plagued prior RTS games, including Warcraft 2 and Starcraft.

On baseless missions, like in previous games, the heroes must survive, and any hero’s death instantly fails the mission. That’s okay in this game, because heroes are sturdy, there’s a lot of healing items on the way, and you only control the hero’s stack with no pressure to multitask. You just methodically advance from the beginning of the map to the end, exploring everything along the way.

However, on missions with a base, things can get frantic, and your heroes can be killed in the fray. In previous games, this created an incentive to keep your heroes back at your base, out of trouble, which negated their whole purpose and didn’t feel exactly, well, heroic. In Warcraft 3, slain heroes can be resurrected back at the base, which is slow and expensive, but at least it means you aren’t punished for bringing them into critical battles. It’s also, very critically, treated as a gameplay mechanic only, like the rest of the RTS abstractions. Heroes die in the story all the time (there really is a lot of major character deaths in Warcraft 3), but nobody, ever, treats the altars as get-back-to-life-free-cards that exist in-story, nor does anyone ever propose or acknowledge the possibility of resurrecting dead characters there.

This is very, very important. Remember this for when we get to Cataclysm.

The user interface deserves praise as well. Quests are highlighted in popup text, their objectives are updated as you make progress, and gameplay tips and hints appear throughout the missions, including brief descriptions of new units (under the title of “NEW UNIT ACQUIRED”) when you first gain access to them. Whoever was in charge of usability and user experience for this game deserves a medal.

The quest tells us to train five grunts, but it’s not actually optimal to do so right away, because it will complete the quest and trigger an event that starts the next one. So I trained four grunts, then led them and Thrall to explore the available part of the map, clearing a gnoll camp and picking up a Scroll of Healing that a hero can use to heal all nearby allies.

The road abruptly ends with a broken bridge. Hmm, I wonder if it’s plot-activated.

Hilariously, you can repair it, even though it’s not what the game expects you to do, and it breaks the intended sequence. What you’re supposed to do is to complete the quest, after which human peasants repair the bridge from the other side, and a human captain and some footmen charge in.

Thrall deduces that the captured leader is Grom Hellscream, and charges into the human camp across the river. You storm in, kill some human footmen and riflemen, and free captive orcs, including two shamans — a new type of caster unit.

Then, suddenly, a message flashes across the screen!

Congratulations, you’ve encountered the much-maligned upkeep mechanic.

Like I said, Warcraft 3 is designed around hero units leading relatively small stacks, and this affected the way unit supply works in this game. In Starcraft, your supply cap is 200, and there’s no real reason not to mass units until this cap, other than your available resources. In Reign of Chaos, the supply cap is only 90, and even then, you’re discouraged from filling it as soon as you can by two “soft caps” — the breakpoints between no, low, and high upkeep.

At no upkeep, each worker gathering gold returns 10 of it per trip. At low upkeep, which triggers when your total used supply exceeds 40, each worker’s trip only yields 7 gold , but the gold mine still has the full 10 deducted — the remainder is simply lost. At high upkeep, which you enter above 70 supply, each trip only yields 4 gold. This acts as a rubber band mechanic: the more units you have, the more of your resource gathering is wasted, slowing down your unit production, while your gold mine is still exhausted at the same rate.

On campaign missions where you want to take your time instead of rushing the enemy base right away, it is often beneficial to stockpile some resources at no upkeep, then quickly build up an army when it’s time to attack.

Here, the enemy has no base. Instead, you need to destroy three guard towers protecting Grom’s cage, after which he is freed, and the Horde is ready to depart.

Grom has an idea: the orcs can set sail on the humans’ own ships. Because they’re nomadic steppe warriors, so naturally, they know how to do that.

Well, that’s unfair. A lot of these orc captives in internment camps probably sailed ships back in the Second War, when naval combat was all the rage. Thrall and Grom somehow load the entire Horde onto these few stolen human ships and depart Lordaeron, and the human lands, for good as the Prophet watches from a nearby hill.

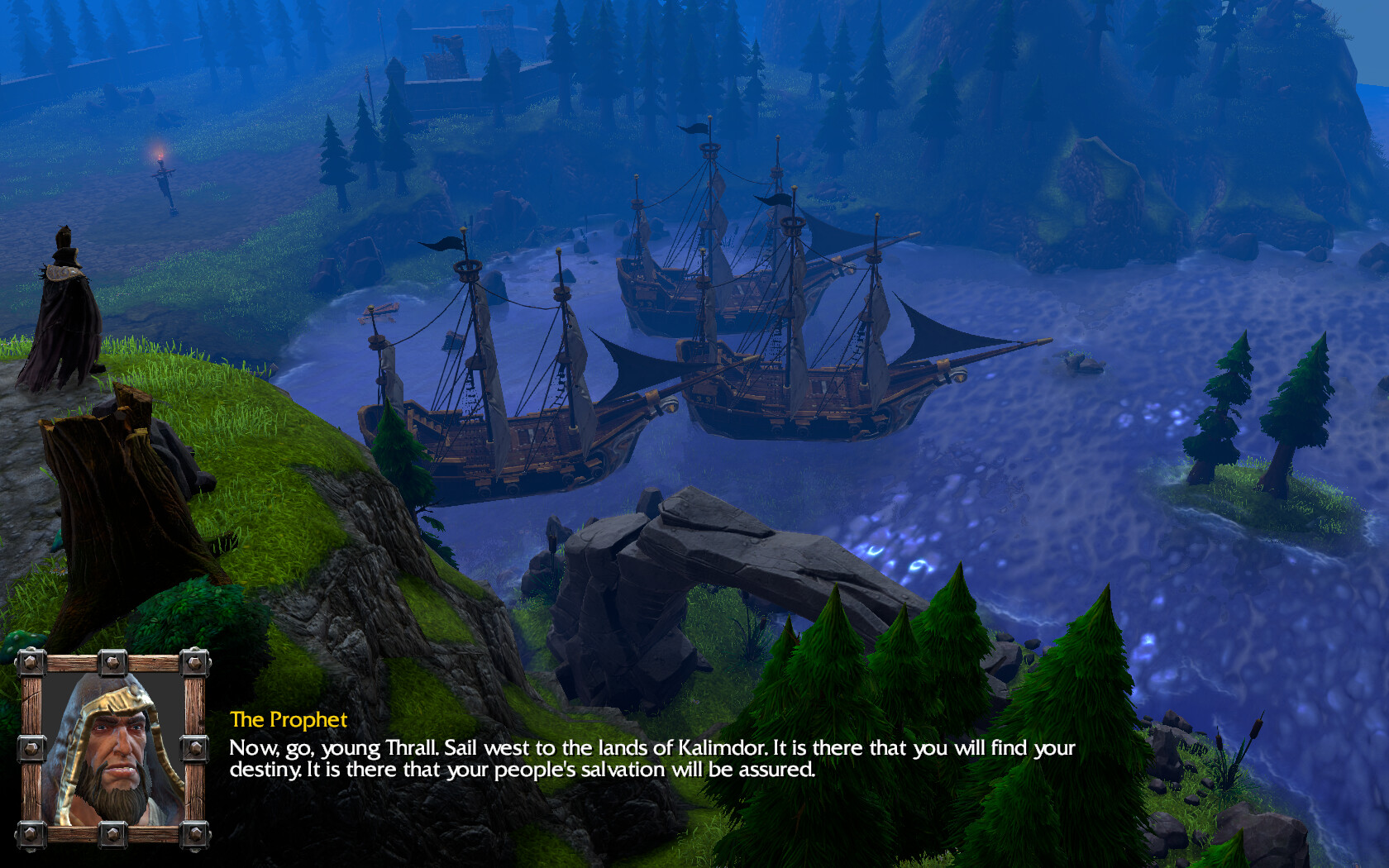

And just to give you an idea of the difference in level of detail, here’s how the same cutscene looks in Reforged. We’ll get to that edition — way, way later, in its due time.

Before we proceed, I should really mention one last thing…

The Horde Identity, Redux

First of all, I should say that the music in Warcraft 3 is superb and gives me goosebumps even now. In my opinion, the orc music theme really fits Thrall’s reformed Horde: the orcs are still proud steppe warriors, but now they’ve cast off their bloodstained past and are striving to find themselves in a new land.

Before, I mentioned the difference between Warcraft 1’s Monster Horde and Warcraft 2’s War Machine Horde. The prologue campaign, following Lord of the Clans, brings us the faction’s current incarnation, which Ramses calls the Rebel Horde. They’re underdogs, hiding in the hills and trying to free the rest of their people — a task at which they eventually succeed. They face a shameful past and an uncertain future. They fight humans not for the sake of fighting, but because they’re forced to.

It seems that this particular version of the Horde has struck a chord with both the writers and the players, and it’s not hard to see why. People sympathize with underdogs and atoners, and despite these qualities, Thrall’s Horde has definitely retained a certain edge and roughness — it just doesn’t revel in them.

We’ll see what this vision of the Horde morphs into in the orc campaign proper.

What’s Next?

And that was part one of the prologue campaign. Next up is part two.

“What part two? Doesn’t this campaign only have two missions?”

Not quite. Make it five.

“Elephant in the Room” by Ferdi Rizkiyanto, Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License.

Screenshot from the webcomic DM of the Rings by Shamus Young.

-

Some units were renamed and got new models between Reign of Chaos and The Frozen Throne — apparently for copyright reasons because Warhammer Fantasy had similar ones. Also, Furion was renamed Malfurion for The Frozen Throne, and Reforged also renamed Grom to Grommash. Reforged applies TFT units, gameplay balance, and character names retroactively to the RoC campaign. It’s a mess, and we’ll look at it when we get to 2020 in the timeline. ↩

-

Thrall does ride a white wolf in Reforged. ↩

-

Though I assume everyone reading this blog already knows the Prophet’s identity, I won’t reveal it until the game does. ↩

Comments

burgundian

A little funny that Warcraft would rename units over IP conflicts with WHFB when WHFB would wind up being canned at least partially over concerns that the IP wasn’t defensible.

Aside from being a green leader of orcs who winds up starting a blood feud with some elves Grom Hellscream and Grom the Paunch certainly don’t have much in common. Probably for the better that Warcraft didn’t try to implement ‘a man so fat he needs to be carried into battle on a cart is (still!) a great champion and slayer of his foes’. Twice.

Leave a Comment