Warcraft Retrospective 15: Lord of the Clans

A year before the release of Warcraft 3, Blizzard faced a problem. Warcraft Adventures: Lord of the Clans, the adventure game that was supposed to bridge Warcraft 2 and 3, was canceled. Its lore, however, was too important to simply discard, as it set up the orc storyline in Warcraft 3. Therefore, Blizzard commisioned a novel adaptation of the game’s scrapped plot. After the first author failed to finish it, Christie Golden was brought in, with only six weeks to write the novel based on Chris Metzen’s plot outline.

And they were in luck. Christie Golden is a self-admitted perfectionist, and it shows.

I can never crank out just a “decent book”… I always want it to be really good, give the readers more than they were expecting. I didn’t want the Thrall/human relationship to be black and white, because those things never are. And, because I knew the races would have to work together in Warcraft 3, I wanted to lay the groundwork for that being plausible.

The book is good. For a book written in six weeks, it’s damn good. It continues the tradition Of Blood and Honor started, helping the Warcraft setting enter its phase of…

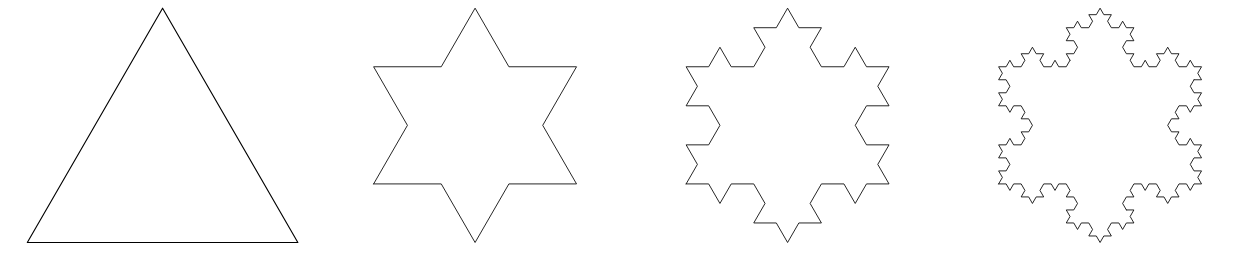

Snowflake Worldbuilding

Flanderization is a process by which previously nuanced characters are flattened and reduced to an exaggeration of their most superficial traits.

After Warcraft 2, the Warcraft setting underwent a rapid reverse-flanderization. The first two games started very basic, with campy aesthetics and completely black-and-white morality of good humans versus evil orcs (though some humans were traitors and some orcs were more evil than others). The story of the First and Second Wars was told in very broad strokes, and the characterization of every character fit in a single paragraph.

With the novels, the characters are acquiring much-needed depth. They focus on specific characters and small corners of the world, giving them more and more detail with each iteration. What seemed to be black and white turns out to be not as simple. The process can be likened to drawing a snowflake, by starting first with the stem, and then drawing increasingly smaller and thinner strokes until the end result turns from a simplistic schematic into a work of art.

Lord of the Clans fleshes out orc culture, gives us a more in-depth look at human social dynamics as represented by a single noble household, and adds much-needed moral variety to both sides of the conflict. Furthermore, it sets a clear narrative direction for the restored Horde to follow, with a sympathetic character at its helm, but hints at possible internal dissent.

Before I dive into the plot, I feel it only proper to praise Christie Golden’s…

Attention to Detail

As much as I appreciate Knaak’s genuine passion for worldbuilding, I found the prose in Day of the Dragon a headache-inducing slog. Lord of the Clans, in contrast, was a joy to read.

The prose is simple to follow, but not simplistic. At times, it’s beautiful, and the dialogue is rife with evocative and quotable metaphors. There are occasional weird word choices, but the narrative flows smoothly, the characters have distinct voices and feel like distinct people shaped by their backgrounds, and I’m immersed in the world. The pacing feels just right. There’s neither an overabundance of detail that bogs down the story, nor does the narration devolve into a Featureless Plane of Disembodied Dialogue when I can’t remember who’s saying what and where it’s all happening. There’s just the right amount of detail, sights, sounds and smells, that I can imagine each scene vividly.

And what detail it is. The language barrier exists and meaningfully affects the plot. Travel takes a long time, even in the relatively small region the story takes place in. The characters get hungry and exhausted, and have to sleep at inconvenient times and forage food. The writer remembers that horses aren’t machines and that courier stations exist for a reason.

We also see the unpleasant sides of life in rural Lordaeron. While the story doesn’t revel in describing Gritty Medieval Realism™ in gory detail, it does deal with some topics that modern Warcraft usually glances over, such as an infant dying of disease, casual sexism (which the story makes clear is wrong), a woman having to disguise herself as a man to join the army, lack of education opportunities in the countryside, and a nobleman abusing his power over his servants in disgusting ways. On the less grim side, there are descriptions of everyday life, of simple joys and chores that give the narration flavor.

The characters are fleshed out, too. You get insight into the inner worlds of all the viewpoint characters: Thrall, Taretha, and Blackmoore. And even if Thrall feels a bit too much of a goody-two-shoes to be true, the story examines — believably, in my opinion — how he came to be that way, and he’s definitely not a flawless hero.

The setting of Lord of the Clans feels like a living, interdependent world, not a bare-bones world where nothing exists that is not explicitly shown to exist in a video game.

To me, it’s a taste of the Warcraft setting that we could have had.

The Plot

Prologue

Durotan, chieftain of the Frostwolf clan, and his wife Draka reminisce about the old days of the Horde from their cold mountain refuge. Like in Day of the Dragon, there is some awkward “as you know” style exposition here; I don’t understand why both Knaak and Golden elected to do their exposition in dialogue rather than narration. Luckily, unlike Day of the Dragon, the awkwardness doesn’t last.

Durotan heads south to tell his friend Orgrim Doomhammer everything he knows about Gul’dan’s treachery: that he sold his people to demons, that he cares for nothing except his own power, and that he secretly puppeteers the Horde through the Shadow Council.

He wants to go alone, but Draka insists on coming with him — and since they have a newborn child, they have to take it with them. This proves to be a mistake. Orgrim listens to everything they have to say, then spares one of his guards to protect them on the way back home. This also proves to be a mistake. The guard turns out to be an agent of Gul’dan and betrays Durotan and Draka to assassins. They cut down the couple and leave the baby to slowly die to the elements.

This also proves to be a mistake.

A human noble, Aedelas Blackmoore, happens to be hunting in the area. He finds the infant orc and smirks. He has a plan.

Thrall’s Youth

As the lord of Durnholde Keep, Blackmoore gets put in charge of Alliance internment camps1 for the captive orcs.

He names the baby orc Thrall, planning to raise him as a slave, and entrusts him to his servant Tammis Foxton and his family. In the Foxtons’ care, Thrall actually almost dies of starvation as an infant until Tammis’s daughter, little Taretha Foxton, realizes that at his age he’s supposed to be fed baby milk, not meat. As luck has it, Clannia Foxton, Tammis’s wife and Taretha’s mother, is breastfeeding a newborn soon and takes Thrall in, too. The human baby, Faralyn, soon dies of a fever, leaving Thrall as Taretha’s sole younger brother of sorts. As soon as he learns to eat real food, however, Blackmoore takes him away, to Taretha’s grief.

Fast forward. Thrall is six years old, kept in a prison cell. Blackmoore belittles him, letting him know that he’s a slave and hitting him to let him know his place. Blackmoore actually assigned Thrall a teacher, Jaramin Skisson, but dismisses him as soon as Thrall learns to read and (barely) to write — and he only does this so he can later teach the young orc strategy, preparing him for the life of a gladiator. During an exercise with a training dummy, Thrall catches sight of young Taretha in the crowd, seemingly alone unafraid of him.

Blackmoore’s frequent mood swings confuse Thrall. Sometimes the nobleman enthusiastically trains him and praises him, and at other times berates him for no reason, with slurred speech and haphazard movements. Thrall ends up accepting that he’s unworthy.

Eventually he moves past training dummies and is set to train with some of Blackmoore’s men under a drill sergeant known simply as “Sergeant” throughout the book. It seems we’re headed for the negative stereotype of his ilk, but instead Sergeant proves to be a stern but compassionate man genuinely interested in Thrall’s growth in skill — though sometimes Thrall falls into a strange bloodlust, barely able to control himself from killing Sergeant, whom he sees with Blackmoore’s face. Reluctantly, at Sergeant’s insistence, Blackmoore allows Thrall to read books to get a better understanding of military strategy. Taretha is assigned to bring the books to Thrall in his cell, and sneaks in a message asking him if he’d like to keep exchanging letters this way; he writes “yes”, in his own blood.

Thrall keeps training, learning over the years that the orcs are being rounded into internment camps, and when he’s twelve, one day, he’s assigned to a training exercise where he’s supposed to play a defiant orc resisting capture. However, a cart carrying actual captive orcs happens to pass near the training grounds; one orc breaks out, shouting something at Thrall that the latter doesn’t understand, and is promptly killed. Thrall is horrified to see for the first time what his kin look like (Blackmoore was careful not to let him near any reflective surfaces, so he only saw humans until now), and begins to understand why humans consider them ugly monsters.

Out of Blackmoore’s entire household, Thrall only sees compassion from Sergeant, who defends him from the bullying of human trainees, and Taretha, who keeps sneaking her letters in his books. The books themselves paint a much larger world beyond the confines of Durnholde Keep — a world of beauty and freedom. Blackmoore forces him to fight in gladiator games and collects the winnings. Secretly, however, he has other plans for Thrall, which he only shares with his young protege Karramyn Langston — spoiled, sycophantic, and just as immoral as him. Blackmoore wants to raise Thrall as a commander for his personal army of orcs — one that would conquer the Alliance for him.

(He’s actually trying to raise his family back into prominence after his father was convicted of treason. He’s torn between a sincere desire to redeem his family name and his grudge against the Alliance. See how it’s not that simple?)

One day, however, Blackmoore makes a fatal mistake. Showing up drunk to a gladiator fight, he makes his slave fight nine gladiator matches in a row; despite Sergeant’s protests, he has come to take Thrall’s victories for granted. With no chance to rest, Thrall is exhausted and covered with wounds by the end, barely managing to win the eighth fight against two giant cats, and finally losing the last one, against an ogre, costing Blackmoore all his would-be winnings. Blackmoore snaps and beats the already gravely wounded orc to near-death. Thrall decides that enough is enough, and writes to Taretha that he plans to…

Escape from Durnholde

Outwardly, Thrall doesn’t show his defiance, but he already longs to see the outside world as a free orc, and to meet his people. Together with Taretha (whom he calls “Tari”), they hatch an escape plan, and one night…

The moons, one large and silver and one smaller and a shade of blue-green, were new tonight.

…Wait. This world has two moons? This world has two moons and we’re only learning this now?

Moving on! Taretha starts a fire to create a diversion, taking care to release the animals first to prevent their deaths. Thrall pretends to sleep until his guards leave, then breaks his cell’s door and, in the confusion, escapes the fortress for nearby forested hills with Taretha’s letters as his most precious keepsake, meeting her at the pre-agreed spot. Crying (and teaching him what tears are), she gives him food, a map of the internment camps, and a crescent moon necklace that he can place in a specific hollow tree if he ever needs her help.

They part on tender terms, as brother and sister in their thoughts. Thrall notices bruises on Taretha’s wrist and asks what happened. She refuses to elaborate because Thrall is so “innocent”, telling him only that she’s Blackmoore’s mistress.

Yikes.

Yes, it means exactly what you think it means. Blackmoore is not only a treacherous, violent, ungrateful alcoholic, dismissive of women (he only lets Taretha be educated because she caught his personal fancy), but he lusts after her and repeatedly rapes her. The book doesn’t actually use the R-word, but the language states it in very certain terms.

And truly, there was no rush. There was plenty of time now to enjoy Taretha whenever and wherever he wished. And the more of that time he spent with the girl, the less it was about satisfying his urges and the more it was about simply enjoying her presence. More than once, as he lay awake and watched her sleep, silvered in moonlight streaming through the windows, he wondered if he was falling in love with her.

He had pulled up Nightsong, who was growing older but who still enjoyed a good canter now and then, and was watching her playfully guide Gray Lady in circles around him. At his order, she had not covered nor braided her hair, and it fell loose around her shoulders like a fall of purest gold. Taretha was laughing, and for a moment their eyes met.

To hell with the weather. They would make do.

He was about to order her off her steed and into a nearby copse of trees — their capes would keep them sufficiently warm — when he heard the sound of hoof-beats approaching.

Keep in mind that — as the narration explicitly states — Blackmoore has known Taretha since she was a little girl.

Extra yikes.

Meanwhile, Thrall heads for one of the internment camps — not the closest one, since that’s what Blackmoore would expect. However, he makes a mistake by sleeping in the open. Six human soldiers find and capture him, taking away all his possessions except for Taretha’s necklace, which he kept hidden. And — this is where Thrall’s mistake will be particularly costly later — the letters are seized, too. Luckily (for now), none of the soldiers can read, so to them, he’s just another orc. They lead him into the internment camp.

It’s not pretty, and Thrall is left completely disillusioned. The dozens or hundreds of orcs in the camp have utterly given up, as if drugged, some of them even sitting in “puddles of their own filth”. He tries to talk to them — in the human language, since he knows only a little Orcish — but they don’t believe his tale and at any rate don’t care, content in their misery. Only one orc with unsettling red eyes has retained enough self-worth to humor Thrall, telling him the tale of the orc clans’ noble past and subsequent fall — the same tale Eitrigg would later tell Tirion Fordring. Thrall learns that the clans of old had spiritualists who worked in harmony with the spirits of the elements and the wilds — called shamans — before the rise of the warlocks.

Blackmoore and Langston are eventually alerted to Thrall’s presence in this camp, and when they arrive, Thrall escapes just in time to avoid being discovered. However, Blackmoore finds Taretha’s letters among Thrall’s seized possessions, and is deeply hurt to discover that she betrayed him. For now, he doesn’t let her know the ruse is up.

Meeting the Warsong

Before Thrall leaves, the red-eyed orc points him to the location of the last free orcs — the Warsong clan, led by Grom Hellscream. When he finds them, Grom’s advisor, Iskar, already knows him as “Thrall of Durnholde”, despising him, and puts him through trials before he’s allowed to see Hellscream. The first one is making Thrall fight three of his finest warriors at once, to the death (Thrall defeats them, but refuses to kill them), and the second one is killing a kidnapped human boy, with the justification that he’ll grow into an enemy of the orcs. This Thrall outright refuses to do. Sergeant, Taretha and the books he read — and the misery he faced growing up as a prisoner — instilled in him a sense of ethics that seems alien to some of his fellow orcs.

(Iskar obviously shows a lapse of judgment here. What if Thrall, hungry and exhausted, lost the three-on-one fight? Grom would probably have Iskar’s head. And why is he throwing three perfectly good warriors on one outcast, considering they’re few in number as it is? It’s clear, however, that he’s simply prejudiced against Thrall and isn’t thinking logically.)

Luckily, Hellscream intervenes via his namesake, er, hellscream before this can get ugly. He orders the boy sent back to where he was kidnapped from, unharmed, and takes Thrall under his wing, teaching him the Orcish language and telling him that the piece of cloth he was found in, depicting a white wolf head on a blue background, is the emblem of the Frostwolf clan, which lives somewhere up in the mountains. Thrall, on his part, observes that Grom is dessicated, physically thin, and seeming to be suffering from the same withdrawal as the captured orcs, forcing himself to stay lucid through sheer willpower.

Grom explains the difference between shamans and warlocks. While shamans request natural phenomena for their aid (yes, an oddly eloquent Grom actually says “natural phenomenon”), warlocks’ magic costs them their own life force.

“But you said that the shamans were disappearing. Doesn’t that mean that the warlock’s way was better?”

“The warlock’s way was quicker,” said Grom. “More effective, or so it seemed. But there comes a time when a price must be paid, and sometimes, it is dear indeed.”

Hmmm…

When learning the language, Thrall discovers that the captive orc back in Durnholde, whose cry he thought was a threat, actually meant “Run! I will protect you!” The adult orc was prepared to give his life so that he, a child, could flee.

However, with Blackmoore on his heels, Thrall has to leave the Warsongs. He heads for the mountains to find his own clan, the Frostwolves.

A Shaman’s Training

And find them he does — again on the brink of exhaustion, with the aid of mysterious ghost wolves. He meets Drek’Thar, the elderly clan shaman who tells Thrall of his true parentage, having led the clan after Durotan and Draka left on their journey and never returned.

After some secret tests of character — testing first his humility, then his self-esteem — Drek’Thar takes Thrall as his shaman apprentice. He explains what kind of affliction has gripped the orcs in the internment camps, in evocative language.

“They are like empty cups, Thrall, that were once filled with poison. Now they cry out to be filled with something wholesome once again. That which they yearn for is the nourishment of the old ways. Shamanism, a reconnection with the simple and pure powers of the natural forces and laws, will fill them again and assuage that dreadful hunger. This, and only this, will rouse them from their stupor and remind them of the proud, courageous line from which we have all come.”

He helps Thrall bond with a female frost wolf, Snowsong, and guides him into hearing the elemental spirits, who, through some more secret tests of character, introduce themselves as the Spirits of Earth, Air, Fire and Water, and an unexpected fifth spirit of…

…the Wilds, actually.

Drek’Thar explains the philosophy of the shaman arts. They only beseech the spirits for what they need, and the spirits do not always answer, nor do they grant selfish requests — like flooding a human encampment full of innocents. Thrall learns to use his shaman training, which opens new senses to him, to benefit the tribe. Once, when they’re low on food, the Spirit of the Stag guides Thrall to a healthy but wounded stag with a broken leg, whom Thrall puts out of his misery and brings to the clan to eat, with great reverence for the Spirit. At another time, Drek’Thar beseeches the spirit of water to spare the clan grounds from an impending thaw of the mountain snow. And at a third time still, Thrall and Drek’Thar to “send energy to the seeds beneath the soil, that they would grow strong and flower in the spring that was so near, and to nurture the unborn beasts, be they deer or goat or wolf, growing in their mothers’ wombs”…

…Wait a minute. I thought that last thing was the domain of a different kind of magic?

Yes, some powers Thrall displays in the second half of this book wouldn’t be thought of as shamanistic in modern Warcraft. Druids haven’t been invented yet — or rather they have been, as the development of Warcraft 3 was well underway, but apparently Christie Golden wasn’t informed of that.

One day, an unknown orc stranger comes to the Frostwolf encampment, acting unusually proud and riling up Thrall to the point that the young shaman challenges him. To Thrall’s surprise, the stranger turns out to wear black plate armor under his cloak, and fights with a large warhammer, which Thrall manages to snatch from his hands — but, reigning in his bloodlust, he stops himself from smashing the stranger’s skull, and, disoriented, loses the fight.

The stranger reveals himself as none other than Orgrim Doomhammer, the former Warchief of the Horde who escaped his prison in Lordaeron. This was yet another secret test of character, and now, having judged Thrall and found him worthy, Orgrim enlists him as his second in command in a daring plan to liberate the orcs in the internment camps.

Storming the Internment Camps

Together, the Warsongs and the Frostwolves manage to liberate three internment camps through the same scheme. Thrall, swallowing his pride and pretending to be just another broken orc, lets himself be captured, then rouses the spirits of the imprisoned orcs with inspiring display of his shamanistic magic (such as making flowers grow from dirt) and inciting them into battle while the free orcs simultaneously attack from the outside.

Soon, however, Blackmoore wises up. He sends detachments of knights to each of the remaining internment camps, ensuring that Thrall and his allies will face heavy resistance no matter where they attack. They end up having a fierce battle in an internment camp where Blackmoore has sent Langston. Thrall opens by beseeching the spirit of all horses to incite the horse to throw off their riders, then sends massive roots to wreak havoc in the camp.

(We also get the names of the two moons: the White Lady and the Blue Child.)

Nonetheless, this battle is much harder than the previous ones, and Orgrim is mortally wounded by a knight’s lance struck from behind. Before dying, he passes his armor, the Doomhammer, and the title of Warchief to Thrall.

Langston is captured in the chaos, shaken and fearing for his life, and Thrall easily makes him spill the beans about everything he knows about Blackmoore and Durnholde’s defenses. Thrall realizes that attacking the internment camps one by one is untenable, and with his army now counting two thousand, decides to cut the head of the snake at Durnholde. He lets Langston go and devises a plan to liberate the remaining orcs without ending too many lives, be they orc or human.

The Battle of Durnholde

By dropping Taretha’s necklace in the hollowed tree, Thrall requests a meeting with her, asking her to relay to Blackmoore that he wants to negotiate. She leaves Durnholde through a secret escape tunnel, reuniting with Thrall for a short while. Unfortunately, Blackmoore, who until now lulled Taretha into a false sense of security, had secretly sent a spy after her who learned of the whole exchange.

Blackmoore greets Thrall from Durnholde’s walkway, completely smashed drunk, and refuses Thrall’s very generous terms of surrender — releasing all the captive orcs in exchange for Thrall returning into the wilds and leaving the humans alone. Instead, he keeps riling his former slave up, blabbers out his plan to betray the Alliance, and Langston, weak-willed coward that he is, misses the opportunity for a peaceful resolution.

“Why’d you do it, Thrall?” he cried brokenly. “I gave you everything! You and me, we’d have led those greenskins of yours against th’ Alliance and had all the food and wine and gold we could want!”

Langston stared, horrified. Blackmoore was now screaming his treachery to all within earshot. At least he hadn’t implicated Langston… yet. Langston wished he had the guts to just shove Blackmoore over the wall and surrender the fortress to Thrall right now.

Remember this scene. We’ll revisit it much later, when we get to Battle for Azeroth.

As his final taunt, Blackmoore throws Taretha’s severed head to Thrall’s feet, and that becomes the last straw. Thrall turns completely livid, and the drunk Blackmoore, suddenly lucid, feels a surge of regret.

It wasn’t supposed to be this way. The orcs on the other side of the now-shuddering gates were supposed to be his army. Their leader, out there screaming Blackmoore’s name over and over again, was supposed to be his docile, obedient slave. Tari was supposed to be here… where was she, anyway… and then he remembered, he remembered, his own lips forming around the order that had taken her life, and he was sick, right in front of his men, sick in body, sick in soul.

The orcs storm the fortress, with Sergeant taking command of the defenses with both Blackmoore and Langston evidently in no condition to lead. Blackmoore tries to escape through the tunnel, but Thrall, having learned of the tunnel from Taretha, cuts off this route and waits for his former master to emerge at the the end leading back to the fortress. He allows Blackmoore the courtesy of an honorable duel, even bringing him his sword, and finally kills him in battle, rejecting one final offer to help him crush the Alliance.

With Blackmoore’s death, Sergeant, declaring Thrall a worthy student, surrenders, followed by the rest of the garrison. Thrall waits until Durnholde is completely evacuated, then, by summoning an earthquake, levels the fortress. He sends Hellscream to give Taretha’s necklace to her family, along with his condolences2, and lets Langston go — on the condition that he takes a message to the Alliance, telling them that he has no quarrel with the humans and only wants them to leave the orcs alone and give them good land of their own to live on.

“Before I killed him, he… he said that he was proud of me. That I was what he had made me. Drek’Thar, the thought appalls me.”

“Of course you are what Blackmoore made you,” Drek’Thar replied, surprising and sickening Thrall with the answer. Gently, Drek’Thar touched Thrall’s armor-clad arm.

“And you are what Taretha made you. And Sergeant, and Hellscream, and Doomhammer, and I, and even Snowsong. You are what each battle made you, and you are what you have made of yourself… the lord of the clans.”

Final Verdict

As I said, I like this book. Its plot is not terribly original — it’s every coming of age story you’ve ever read, crossed with every “living among spiritual natives” story you’ve ever read or watched — but it’s the details and the insight into the characters that sell it.

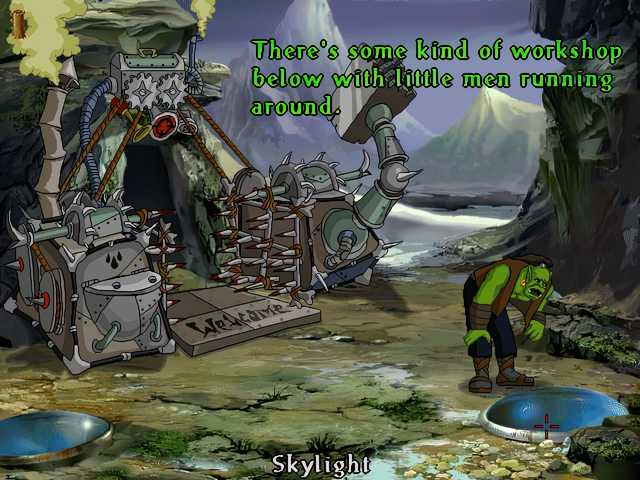

And it’s especially amazing when you consider the game the story was adapted from. Warcraft Adventures was not only cartoony and simplistic, it was outright silly, rife with visual puns (“when pigs fly”), zany aesthetics (Deathwing smoking a hookah), and plots worthy of Saturday morning cartoon villains. In the game, the cause of the imprisoned orcs’ lethargy was not withdrawal from demonic bloodlust. Instead, Blackmoore kept the orcs pacified by striking a deal with Rend and Maim to keep the orcs drunk on black ale in exchange for giving them one hundred orc slaves per month.3

The tone of the book is anything but silly. It’s contemplative and somber. And the Blackmoore of the novel is not a Saturday morning cartoon villain. At all. Instead, we continue the themes of banality of evil that began in Of Blood and Honor. Though Grom compares Blackmoore with Gul’dan, he really isn’t. Gul’dan was a cackling megalomaniac who sold his people to demons and doomed his world in a mad quest for power. Blackmoore is just a despicable person indulging in power that he doesn’t deserve and didn’t earn. And even then, you can be left sorry for him. This is a story where no one is evil to the core — not even Blackmoore.

Why, though, if Blackmoore’s aim had ultimately been to win Thrall’s complete loyalty, had he not been treated better? Memories floated into Thrall’s mind that he had not recalled in years: an amusing game of Hawks and Hares with a laughing Blackmoore; a plateful of sweets sent down from the kitchens after a particularly fine battle; an affectionate hand placed on a huge shoulder when Thrall had conquered a particularly tricky strategic problem.

Blackmoore had always aroused many feelings in Thrall. Fear, adoration, hatred, contempt. But for the first time, Thrall realized that, in many ways, Blackmoore deserved his pity. At the time, Thrall had not known why it was that sometimes Blackmoore was open and jovial, his voice clipped and erudite, and sometimes he was brutal and nasty, his voice slurred and unnaturally loud. Now, he understood; the bottle had gotten its talons as firmly into Blackmoore as an eagle’s sank into a hare. Blackmoore was a man torn between embracing a legacy of treachery and overcoming it, of being a brilliant strategist and fighter and being a cowardly, vicious bully. Blackmoore had probably treated Thrall as well as he knew how.

We could have had this instead, but thankfully, we didn’t. Of Blood and Honor and Lord of the Clans paved the way for turning Warcraft from a purely campy setting into one where both silly and serious stories could be told, depending on the writer.

We’ll talk about the ramifications of that at a later time.

What’s Next?

Technically, Warcraft 3 comes next, but it will have to wait another entry. The Last Guardian was released after that game, but thematically it’s still part of the four in-between novels, being an expanded look at some of the events of Warcraft 1 through the eyes of Khadgar, who, as it turns out, was Medivh’s apprentice, and setting up some important plot points for the third game.

I’m going into this one completely blind. We’ll see how it goes!

Screenshots from Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back and Captain Planet and the Planeteers.

-

This term, which will become standard going forward, is introduced in the book, fitting its real-life usage as military camps for enemy civilians and prisoners of war. The game called them “reservations”, a word with very different connotations. ↩

-

Thrall’s practice of using Grom for menial tasks will bite him in the backside much later. ↩

-

There were other oddities in the game’s lore that didn’t make it into Warcraft as we know it. For example, Alexstrasza and Deathwing were simply powerful dragons before Day of the Dragon fleshed them out. Alexstrasza in Warcraft Adventures was much meaner than the noble Dragonqueen we know now, and Deathwing was her rebel son. She also pledged herself and her red dragons to Thrall’s Horde after Thrall killed Deathwing by himself. ↩

Leave a Comment