Warcraft Retrospective 12: The Game That Never Was

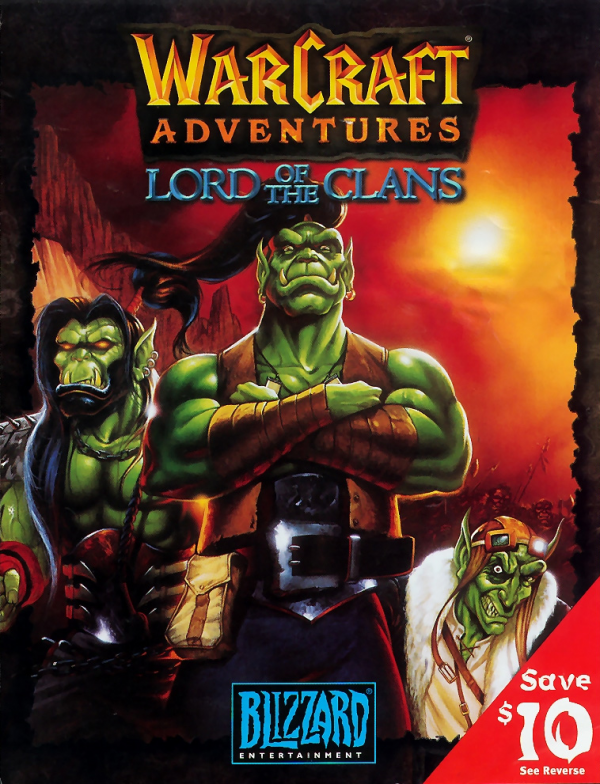

Like we saw last time, after Warcraft 2, Blizzard wanted to branch out beyond the real-time strategy genre1, and their sister company Capitol Multimedia convinced them to use the Warcraft license for a point-and-click adventure game. The project was named Warcraft Adventures: Lord of the Clans, and once again, Chris Metzen was put in charge of the writing.

Everything about this game was unusual for its setting. Whereas formerly we directed battles that decided the fate of an entire continent, now we were going to control a single character: Thrall. An orc. And a good guy — the first sympathetic orc introduced in Warcraft!

How did this happen? In both previous games, the orcs were unrepentant and unashamed antagonists leading wars of conquest and encroaching on human lands. Individual orcs were conquerors, demon-worshipers, opportunists, backstabbers, battle-crazed maniacs, or assassins. Their designs ranged from “monsters” to “endearingly ugly”. They were clearly meant to be the bad guys through and through. What happened?

To understand this, we’ll need to talk about orcs as a fantasy concept.

What Are Orcs, Really?

Like many other fantasy concepts that we take for granted today, orcs as we know them were codified by J.R.R. Tolkien for his Middle-earth mythos and stories.2 Though Tolkien never divulged the reasons why he introduced them into his world3, scholar Tom Shippey believes it was for no other reason than to populate Middle-earth with “a continual supply of enemies over whom one need feel no compunction”. Tolkien fought in World War 1, where the enemy soldiers were young men conscripted to fight for the ambitions of politicians interested in redrawing national borders. His orcs, in contrast, were servants of a Dark Lord, a very tangible manifestation of Evil as a cosmic force, which had and needed to be fought.

And this was fine for Tolkien’s earlier works. But as he developed Middle-earth, it acquired nuance.

Part of it was Tolkien’s Catholic beliefs. As an atheist, I don’t feel qualified to talk about them, so I’ll try to convey the gist of the issue without bringing real-life religion into an already morally tangled topic. I’ll focus on what’s relevant to the evolution of Warcraft.

Tolkien was inspired by old-time mythologies, sagas, and fairy tales. They were, of course, written by humans, here in the real world, fueled by our fascination with the unknown and mysterious, and as such, they were largely human-centric. The mythmakers saw themselves and their fellow humans surrounded by an uncharted, dangerous world, which the collective imagination populated with nymphs, faeries, trolls, ogres, dragons, trickster spirits, and many more instances of the Other. They were different. They were not us. They were primarily defined by their interaction with humans, and it was okay if they had no consistent internal psychology or discernible motives. The Fair Folk kidnapped and replaced human children because that’s the thing the Fair Folk do, not necessarily because the mythmaker’s imagination imbues them with a consistent and developed culture in which such behavior makes sense.

One of the clever things Tolkien did with his constructed mythology was breaking away from the perception of non-humans as an inscrutable Other. His world is not human-centric; rather it’s Spoken-centric. The Silmarillion is elven mythology and history. It shows Middle-earth and its peoples through the eyes of elves, who see themselves as the default case and everyone else as unusual. The stories of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings are told from the perspective of hobbits, to whom the humans of Middle-earth are strange outsiders, to say nothing of elves and dwarves. More importantly, the elves, dwarves, and hobbits of Tolkien’s world are all portrayed as people. They have cultures, in-universe beliefs, families, their own heroes and villains, and their individuals have ethics, inner worlds, imaginations, and motivations for what they do.

If we take this for granted now, it is thanks to decades of exposure to Tolkien imitators.

But while Tolkien expanded his world beyond the human-centrism of his predecessors, the forces of tangible personal Evil still needed evil minions for his protagonists to fight; they were a mechanical necessity of his stories like Batman’s inability to ever save Gotham City for good. And it presented a thorny question…

Are Orcs People, Too?

Wikipedia covers Tolkien’s moral dilemma, including the underlying Catholic background, in more detail than I will here. What matters to us is that Tolkien was deeply, deeply distraught by the idea of an inherently evil race in his works, but didn’t arrive at a satisfactory solution until the end of his life. He considered different origins for orcs to allow them to fill the narrative role he put them in, but none felt adequate.

The different origins Tolkien considered boiled down to:

- Orcs are merely beasts given a humanoid shape. In this case, they have no morality of their own and simply do what they’re told by their masters. This could have sufficed, had The Silmarillion been an isolated work. However, Tolkien cut off this line of retreat by having orcs speak in The Hobbit4 and by humanizing some individual orcs in The Lord of the Rings, even giving them some moral judgment.

- Orcs are people, but created wholly evil and incapable of good. In this case, killing them on sight is not only permissible but can be argued to be a grim necessity for the other races. However, this option greatly disturbed Tolkien. In his world, nobody is born evil, not even Sauron, not even the Satanic archetype whom Sauron once served. Also, for complicated cosmological reasons, Evil in his world cannot create anything from scratch, only twist and mock what came before it, so the orcs had to be corruptions of something.

- Orcs are people with the capacity to choose between good and evil. Even when de facto all orcs seen in Tolkien’s works choose evil, or more correctly are pressured into it by the will of their masters, the mere possibility that they can be redeemed means they must be treated with mercy and compassion, even if their actual redemption lies beyond the means of any of the characters in the story.

It’s also important to note that Tolkien didn’t conceive his orcs as powerful and menacing. They were pitiable, in fact shorter and individually weaker than humans, and only dangerous in large numbers. They were bullies, foul-mouthed and driven by selfishness and envy and spite for everything beautiful; they were to humans what Gollum was to hobbits. In his letters about the real world and in appendices to The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien often used orcs as a metaphor and was not subtle at all about which human qualities he implied.

But Orcs and Trolls spoke as they would, without love of words or things; and their language was actually more degraded and filthy than I have shown it. I do not suppose that any will wish for a closer rendering, though models are easy to find. Much the same sort of talk can still be heard among the orc-minded; dreary and repetitive with hatred and contempt, too long removed from good to retain even verbal vigour, save in the ears of those to whom only the squalid sounds strong.

I’m saying this to underline that Tolkien’s orcs weren’t a stand-in for real-world tribal or nomadic cultures. Indeed, Sauron’s orc soldiers had a kind of organization to them that was fairly modern-coded, with formations and dog tags, though with abysmal discipline and rampant backstabbing. Tolkien approached his creations with far more nuance than the pop culture fantasy that came after him — stories that Ursula K. Le Guin dismissively called “Belch the Barbarian”.

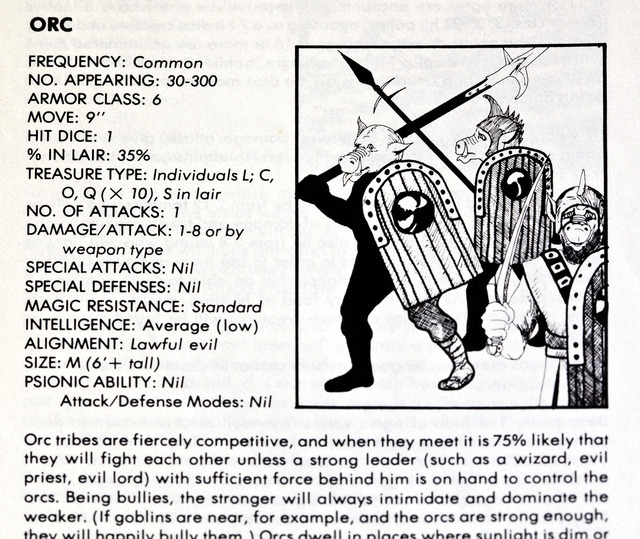

This is a screenshot from Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, released in 1977, four years after Tolkien’s death.5

Now, I love Dungeons & Dragons as it exists now. I wouldn’t have played and DM’d countless 5th edition games if I didn’t. But I also realize that the early editions are really unfortunate by modern standards, paper-flat, and heavily founded on protagonist-centered morality.

Old school fantasy RPGs rejected human-centrism6, but instead they divided their fantasy world along a different kind of “us versus them” line. On one side were the Adventurer Races, flanderized versions of the Tolkien staple of humans, elves, dwarves, halflings, and other mostly-human-looking-and-not-conventionally-ugly races. They were “us”, the good guys. The role of “them” was filled by the Monster Races: orcs, trolls, goblins, kobolds, gnolls, and the like. Those existed only as bad guys whom the adventurers could kill without remorse for the sake of that sweet, sweet treasure and experience points. D&D co-creator Gary Gygax was surprised to learn that more modern players even considered killing baby orcs a moral dilemma at all. Even official 5e materials describe orcs, gnolls, and goblinoids as innately inclined towards evil because they were created by evil gods.

Warcraft originally borrowed its orcs from Warhammer Fantasy, where, again, the race had an inborn tendency towards evil. That was their portrayal in Warcraft 1 and 2, though in practice, the cartoony art style often made them look more endearing than menacing, in a “Saturday morning cartoon monsters” kind of way. I don’t think the creators of Warcraft 1 thought much about the decision to use orcs as the evil faction. Orcs were a convenient, easily understood shorthand for “the bad guys”, and the bright green skin of Warhammer-style orcs made them recognizable with the limited resolution graphics.

But now, with Warcraft Adventures, the clear-cut, black-and-white opposition between the good Alliance and the evil Horde makes way for a new, very important chapter in the history of the franchise…

In Which Chris Metzen Redefines the Word “Orc”

This is a screenshot from the Warcraft movie, which applied the modern Warcraft orc concept to the events of Warcraft 1 and made them almost unrecognizable in the process. In Warcraft Adventures, we were supposed to play as the son of the guy on the left.7

Chris Metzen was not subtle about his vision. Just like he stated from the get go that Warcraft Adventures meant to set the stage for Warcraft 3, so did he say outright that Thrall’s quest was meant to rediscover the original, uncorrupted orcish traditions.

In general, Metzen and his teammates are trying to abolish the stereotype that Orcs are, as he puts it, “brutal, savage dudes who use foul language.” In Warcraft Adventures, they have a complex culture that is rooted in shamanism and a connection to the land. In fact, Metzen draws a connection between Orcs and Native Americans. “We want to show the Orcs as the best that they can be,” says Metzen. “They aren’t the villainous ones in this chapter, but they still will have an edge, a hard edge.”

Under this revised backstory, the orcs were actually not a race of evil conquerors before they turned to conspiring with demons and practicing black magic. They were a tribal, shamanistic culture living off the land.

This is, strictly speaking, a retcon, but a palatable one. Technically it doesn’t even contradict Warcraft 1 and 2, whose accounts of the orcs’ backstory are told in-universe by Garona (an agent of the Shadow Council, who doesn’t know the full story) and Gul’dan (a power-hungry warlock consorting with demons). Not the most reliable of narrators. The revised origin does ennoble Warcraft orcs in a way, but at the cost of breaking virtually all ties with the conventional fantasy concept of orcs as it existed before them.

If I told you that my elves have horns and antenna ears, a culture based around mathematical concepts, live about as long as humans, and speak in (rolls dice) valley girl slang, you would rightly question why I even called them elves. This would be true even if they wore graceful robes, spoke a flowing language with lots of l and th sounds, and traced their ancestry to Tolkien through an unbroken chain of memetic mutation.

And that was the point of me writing this whole long-winded introduction. Warcraft Adventures fleshed out Warcraft orcs, yes, — but it did so by redefining the word “orc” to refer to “noble barbarians”, hulking tribal nomads with proud warrior and shamanistic traditions and very definitely people of moral worth, rather than pitiful, petty, barely-even-human wretches. Though this particular concept has since been popularized by other fantasy media that came after, it’s best to view Warcraft-style orcs as their own mental category that has little in common with Tolkien and D&D orcs other than the name.

And I mean, it’s not like Blizzard is going to retroactively overwrite any more Warcraft races with forgotten uncorrupted versions, right?

The Actual Game

Like I said, I’m not going to play through Warcraft Adventures, as it was never officially released and therefore I can’t legally obtain a copy. For this post, I’ve relied on pre-release materials and third-party sources. Though I haven’t watched it, ThunderBob on YouTube has a playthrough of a fan remaster of the leaked development build, complete with cinematics.

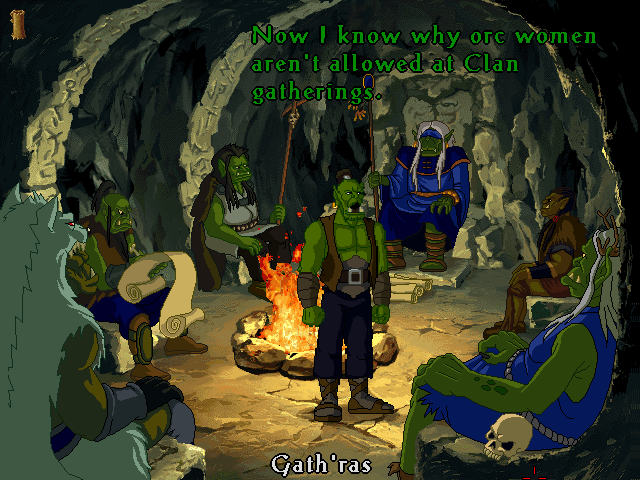

Already the trailer properly sets the mood. It’s a cartoony game. Not the modern Warcraft aesthetic we know from Warcraft 3 onwards, but a different cartoony aesthetic of 1980-style animated series.

The intended overall plot of Warcraft Adventures was retold by Bill Roper in an inteview to GameSpot. It’s reproduced verbatim by the Warcraft Wiki page on the game, with some analysis on the game’s deviations from later Warcraft lore.

We’re back on Azeroth. This makes sense, since Draenor was destroyed at the end of Beyond the Dark Portal. After the Second War, the Alliance, showing mercy to the surviving orcs, put them in reservations, letting them live there and work the land as long as they didn’t cause much fuss. But to the orcs, proud steppe-roamers as they were, this way of life was antithetical to their nature. They fell into lethargy, despair, even alcoholism.

Our protagonist, Thrall, is an orc raised from infancy by a scheming human noble, Lord Aedelas Blackmoore of Durnholde, who hoped to raise him into a general of his own personal orc army to crush his opposition. Through solving puzzles, including disguising himself as a human at one point, Thrall escapes captivity and rediscovers his heritage as the son of Durotan, the late chieftain of the noble Frostwolf clan…

…Wait a minute. Who of the what clan now?

Neither Durotan nor the Frostwolf clan were mentioned in the previous two games. They were inserted into the backstory of orcs for this game specifically. I don’t know why; it’s not like Warcraft 2 didn’t have a plethora of already established clans to choose from. I guess they were too savage and warlike for the story they wanted to tell here.

Anyway, Thrall meets some characters old and new in a different context. Orgrim Doomhammer apparently escaped captivity, because he’s now a hermit in a hut on the outskirts of Durnholde. The goblin engineer Gazlowe crashes his zeppelin nearby. Gnomish inventors practice their WACKY SCIENCE.

And Zul’jin… runs a curiosity shop for some reason, full of references to Warcraft 1 and 2.

Here we see one of the problems with this game. It features familiar characters aplenty, but the context in which we encounter them is often outright weird. Zul’jin has apparently stepped down from fighting. Alexstrasza is found on Crestfall near pre-retcon Kul Tiras…8

And Deathwing is in Blackrock Spire.

…Wait, what?

How is Deathwing alive, let alone back on Azeroth? Last we heard of him, he either accompanied Ner’zhul to new worlds (in the orc campaign) or was turned into a pile of dragon meat by the Alliance Expedition (in the human campaign). Either way, he should be beyond the Dark Portal. Is it even explained in this game?

Grom Hellscream and the Warsong clan are also on Azeroth, guarded by a two-headed ogre. Unlike with Deathwing, this makes sense here. The Warsong and Shattered Hand clans were abandoned on Azeroth in the orc campaign and not encountered on Draenor in the human campaign. In fact, both clans are encountered in this game.

Eventually, Thrall finds the Frostwolf clan in the Alterac Mountains, learns of their shamanistic traditions, and recovers his father’s axe.

In case this wasn’t obvious, the game isn’t subtle about the Native American parallels at all — and they’re not of the good, well-researched kind, but of the pulpy pop culture kind. The orcs have shamans9 and a council of elders. They once roamed the steppes. Now they’ve been put in reservations, as the game insists on calling their habitats, and have turned into impoverished drunkards. The only way this could be any more on the nose would be if they called humans “palefaces”.

This fits with what I understand about Chris Metzen’s creative process at that time. He drew inspiration from a variety of source material, but unfortunately, the source material was often itself full of third-rate cliche storms. Often he was inspired by popular movies and comic books. In this particular case, he described Thrall’s quest in Warcraft Adventures as “Braveheart meets Spartacus meets Dances With Wolves”, all movies known for their impeccable historical accuracy10. Metzen was very much into pop culture, and this resulted in many elements of Warcraft being derivative of stories that were already derivative of better stories themselves.

Other locations visited in the game include Grim Batol, an abandoned base of the Old Horde11, and Northeron Pass, a Wildhammer dwarf aviary where one of the puzzles requires Thrall to magically disguise himself as a dwarf because… shamans can totally do that now, apparently.

As the game continues, Thrall’s inventory gets more and more overstuffed with all kinds of random junk — including spells, which are also considered items in the inventory. Some of them are counterintuitive, with spells requiring the player to target Thrall instead of the obvious target. It’s all fairly janky.

Eventually, the story would see the orc clans rallying under Thrall and the Frostwolf banners, rebelling against Blackmoore, and storming Durnholde Keep to free Thrall’s fellow inmates.

So Why Was It Canceled?

Different people tell different stories. From what I can tell, instead of having a single reason for its cancellation, Warcraft Adventures suffered a death of a thousand cuts.

In 1996, Blizzard already had its hands full in developing Diablo and Starcraft, both of which would become hits and spawn sprawling franchises of their own right. The animation for Warcraft Adventures was outsourced to Russian studio Animation Magic, a subsidiary of the very same Capitol Multimedia that pitched this game’s idea to Blizzard in the first place. Unfortunately, the quality of its animation output was very… uneven.

Keep in mind that this was before the widespread availability of the Internet. Blizzard, most prominently Bill Roper, had to communicate with animators on the other side of the globe. This resulted in problems with translating Metzen and Roper’s vision as intended. The game suffered delays. The language barrier was a problem as well. The traditional 2D animation was time-consuming to produce and costly to change in response to requirements.

Blizzard was also inexperienced in designing adventure games. The gameplay ended up subpar. The puzzles were repetitive and often thematically divorced from the setting and the story. There wasn’t much mechanical variety either — in a time when competing adventure games were getting creative with their design.

As I recall, there was one puzzle that resulted in Thrall using a flower to attract some creature he was trying to capture. Needless to say, that was so far from what an Orc warrior would be doing, so we had to go back to the drawing board.

~ Bill Roper

In early 1998, as a last-ditch effort to save the game, Bill Roper called for adventure game designer Steve Meretzky, who spent two heavily-crunched weeks going over the game and suggesting changes that could be implemented without going hopelessly over budget as it was. The proposal would have involved a user interface overhaul, improvements to the puzzles, and changes to the art and dialogue. Blizzard worked on Warcraft Adventures for three more months, but the release date kept slipping. In the end, even with Meretzky’s proposed changes, the game would have been merely adequate. And merely adequate wasn’t enough.

By the time Warcraft Adventures would be in a shippable state — and we’re talking physical copies here, long before the advent of digital game stores — the adventure game genre lost its steam. The Curse of Monkey Island, developed by LucasArts and released in late 1997, sold below expectations.

In the end, realizing it would simply not be commercially viable even if completed, Blizzard axed the project. Five months later, Grim Fandango, an innovative 3D adventure game from LucasArts, failed to sell as well, despite also having superior production values to Blizzard’s unreleased game. With LucasArts pulling out of the genre, the age of adventure games was effectively over.

Warcraft Adventures became a cautionary tale to the company. After the success of Warcraft 2, it had money to throw around, but it was still learning to use that money wisely.

The important thing is that classic Blizzard — the Blizzard that gave us Diablo, Starcraft and eventually Warcraft 3 — recognized that Warcraft Adventures was simply not viable to release, and decided to cut its losses. Then twenty-two years later, twilight era Blizzard would just outright overwrite a beloved game with a rushed, buggy, subpar replacement.

Closing Thoughts

As flawed and at times culturally insensitive as it is, having read about The Game That Never Was, I’m sad that it never was.

If we were to play through Thrall’s plight, daring escape and maturing into a leader, even in the comedic tone of Warcraft Adventures, instead of merely reading about it in a book, then we could have appreciated the game as the start of a new saga in the Warcraft universe, different in tone and themes than the saga that preceded it. We could have seen for ourselves just how different Thrall’s reformed Horde is from the Horde of the First and Second Wars, and develop more empathy for it. We would have had a bridge between Warcraft 2 and Warcraft 3, which basically starts where Warcraft Adventures was supposed to end.

Ah well.

Next we have four novels released after Warcraft 2 and leading into Warcraft 3. These are Of Blood and Honor, Day of the Dragon, Lord of the Clans12, and The Last Guardian. I’ll go through them in order of publication, starting with the first one, Of Blood and Honor. Get ready to see more sympathetic orcs!

-

They didn’t entirely put their RTS games on hold, seeing how Starcraft began development in 1996, the same year Beyond the Dark Portal was released. ↩

-

Here’s a fun fact: the English words “orc” and “ogre” are both descendants of Latin Orcus, the name of a god of the underworld. I don’t know if the author of Chronicle 2 knew about this, but making the words related in-universe, with both orcs and ogres ultimately descending from Grond, was really clever. ↩

-

To my knowledge. Correct me if I’m wrong. ↩

-

Orcs are called goblins in The Hobbit, but in-universe these are explicitly different names for the same creatures. ↩

-

Quick, someone pitch a race of pig people to Blizzard! We can call them “porcuar” or something. ↩

-

Somewhat. Gary Gygax had some really unfortunate human superiority ideas for old school D&D. ↩

-

Not the wolf. ↩

-

To their credit, they reproduced the Warcraft 2 map of the continent pretty much verbatim. It will be a while before continent shapes will start undergoing retcon after retcon. ↩

-

Which is really a Siberian term, but it came to be associated with Native Americans through pop cultural osmosis. ↩

-

Not. ↩

-

And fittingly, it looks like a typical Warcraft 2 base. ↩

-

An adaptation of this game. We’ll take a closer look at the story it would have had. ↩

Leave a Comment