Warcraft Retrospective 3: Warcraft 1, the Orc Campaign

Based on the somber, detailed language of the Warcraft 1 manual, you might expect the game itself to have washed-out colors tending towards grey and brown, and an overall eerie, unsettling atmosphere slanted into horror.

Not quite, it turns out. But before we can actually run the game, we first have to proceed with…

Installation

Warcraft 1 is a 16-bit DOS application. Windows 95, Microsoft’s first 32-bit OS for home computers, won’t be released for another year, and the Windows we do have at this point is a 16-bit graphical shell for MS-DOS. This means there’s no way to run the game on modern 64-bit operating systems without using a DOS emulator.

The copy of Warcraft 1 that I played for this article comes from gog.com1, and it just unpacks the original game files and sets up a preconfigured DOSBox to run it. Had I used Windows, that would have been the end of it. Under Ubuntu Linux, however, I had some problems with running the bundled copy of DOSBox under Wine, so I installed a native Linux version of DOSBox. Then the game ran and had sound effects and voice acting, but no music. I correctly guessed that the game’s music was in the MIDI format2, and after some googling, I found a way to configure the Linux version of DOSBox to use the FluidSynth MIDI synthesizer. That did it, and I got the full experience.

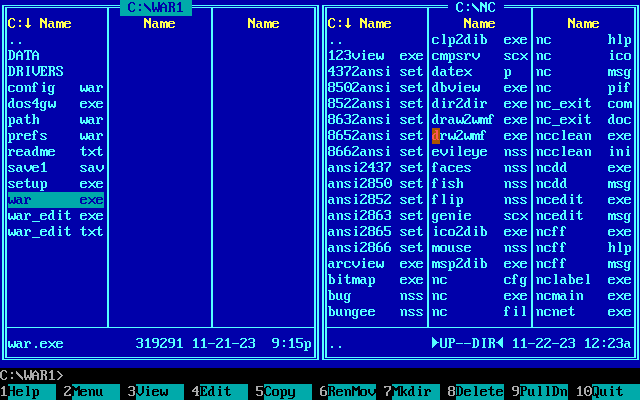

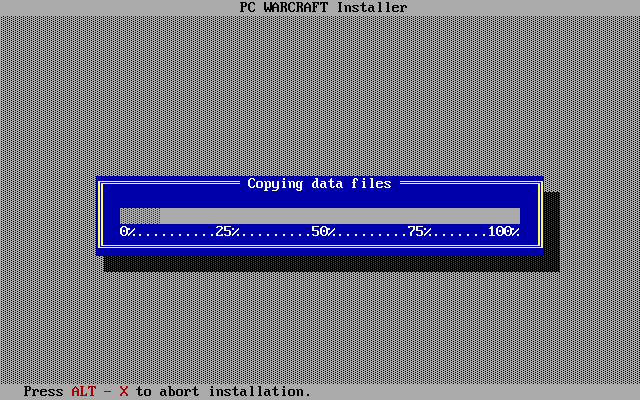

Had we instead installed Warcraft 1 from the original installation media directly under DOS, the process would have been more involved. The free demo includes an install.exe file that gives an idea of what it’s like. It’s a text mode DOS installer, simple with no frills, and when you run it, DOSBox painstakingly emulates a slow hard drive typical of that era.

One way or another, the game is installed. Let’s run the executable, named, fittingly enough, war.exe, and see for ourselves…

The Starting Experience

Warcraft 1 starts with an intro cinematic that’s really low-budget for what we’re used to from Blizzard. It’s animated from a few still frames. A generic castle, a spooky swamp, a portcullis. Notably, the opening narration ends with the words “welcome to the world of Warcraft” long, long before there were any plans to actually make a game by that name.

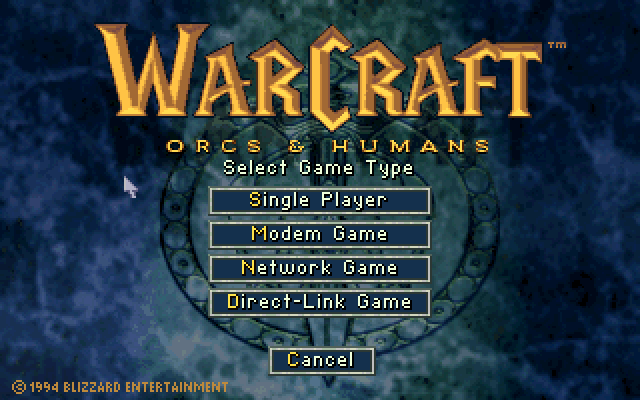

In the main menu, you can choose a single-player or multiplayer game, though all means of communication that this game supports (modem, IPX, and COM port direct link) have long become obsolete. Nonetheless, it is supported, as are single scenarios. The single scenarios are variations on three themes (forest, swamp, and dungeon), and there is no map editor.3

What really interests us, however, is the campaigns, because that’s where the story is told. We’ll start with…

The Game World

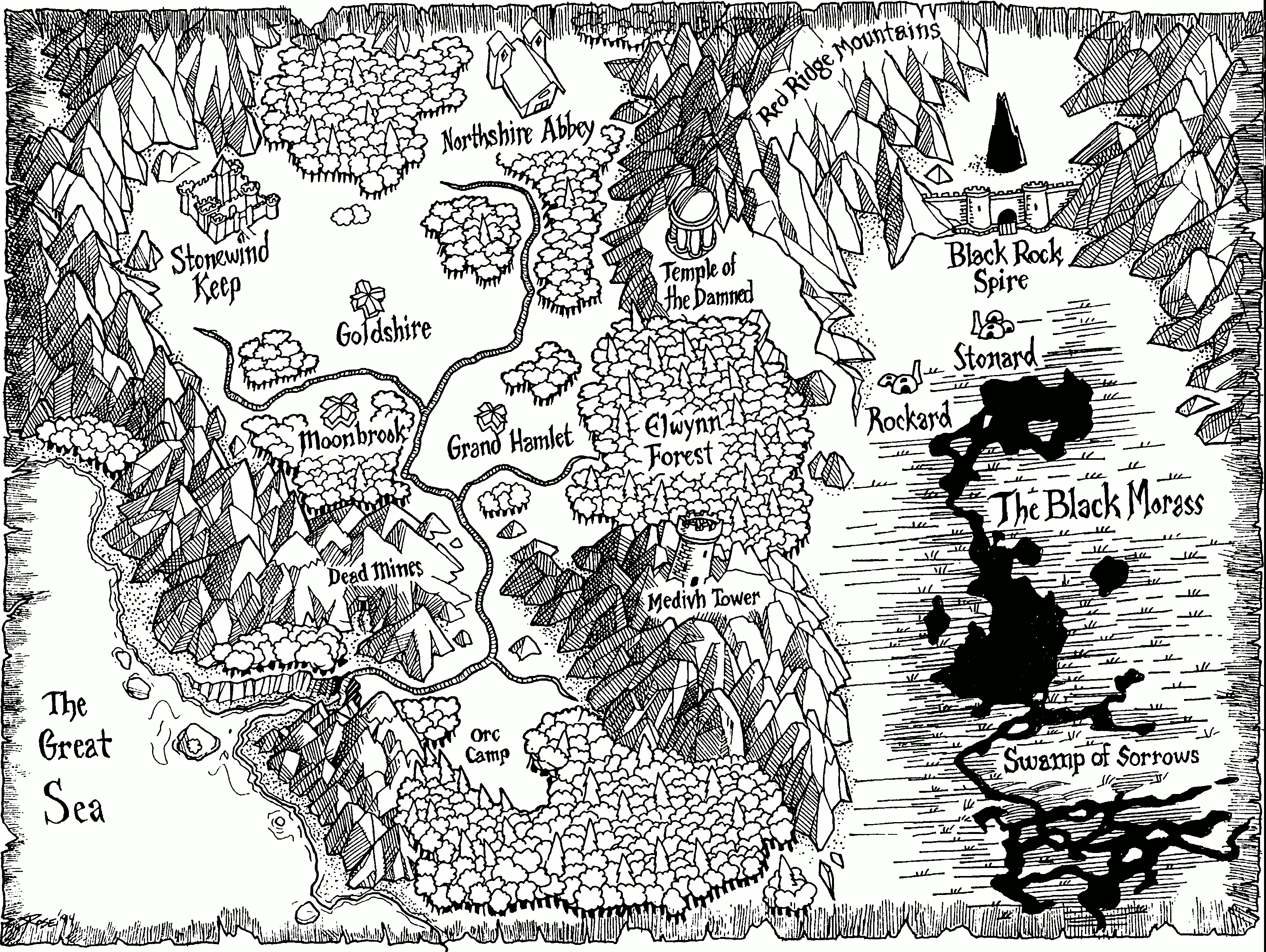

Warcraft 1 takes place in the human Kingdom of Azeroth, which is being invaded by the orcs. Its map is actually contained in the manual, but focusing on it in the previous post would have made an already long post even longer.

This isn’t quite the map we remember from World of Warcraft. The geography is all jumbled. Stormwind4 is landlocked and surrounded by mountains, contradicting not only modern lore but even Warcraft 2. Stranglethorn Vale hasn’t been invented yet, though it could just be there off the map. The Swamp of Sorrows and the Black Morass (future Blasted Lands) switched places in later lore. But already, it’s very clear that this map represents only one small corner of the world, not all of it.5

This map is effective at establishing the mood. The good guys live in a lush forest ripe for the taking, and the bad guys live in a spooky swamp, which, as the manual implies, formed there by the virtue of the orcs living there. If the orcs succeed in conquering the human lands, the same fate awaits it, too.

The Orc Missions

As I said before, the bulk of the lore of Warcraft 1 is contained in the manual. The game itself is relatively light on lore, and the missions are fairly generic. Nonetheless, there are some interesting tidbits.

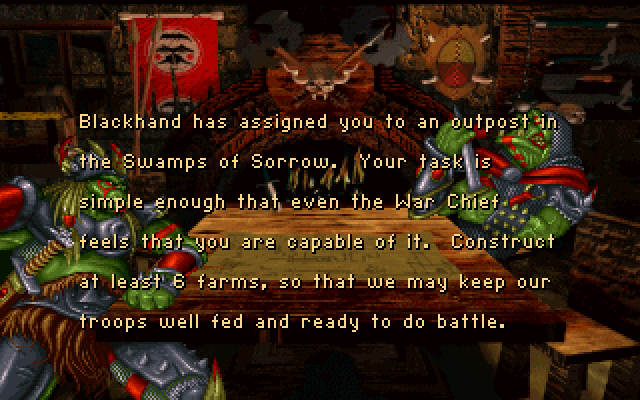

Every orc mission begins with the same limited-animation background of two orcs at a table. These aesthetics, to me at least, notably contrast the somber and serious atmosphere of the manual. They look cartoonish, like a pixelated screenshot from Disney’s Adventures of the Gummi Bears. The Warcraft 1 orc aesthetics, including these horned helmets, were inspired by Warhammer Fantasy and Blizzard’s previous game The Lost Vikings, and it shows.

The limited production budget is evident. All voice acting in the game was done by one guy6. Orc combat units share the same quotes consisting of growls and words in Orcish, and they get old really fast.

Nonetheless, there are some interesting elements here that didn’t return for later games. Every mission briefing ends with an animated 3D map, zooming in on the particular region where the mission takes place, which rises up from the map, Game of Thrones style. So the map in the first mission starts blank, and by the end of the campaign, you will see it all in its 3D glory.

The Gameplay

First, I should give credit where credit is due. The animators did an impressive job for what they had to work with.

The screenshots in this post are made at a resolution of 640×400, but Warcraft 1 was designed to run at resolutions as low as 320×200. Therefore, on the screenshots, every apparent square “pixel” is actually a block of 2×2 pixels. Under these constraints, the artists succeeded in making the units and buildings as distinctive as they could. The bright green skin of the orc units immediately distinguishes them from both the environment and the human units. You never get confused which team is which.

Admittedly, I was at first confused between the units. Is this particular blob of green pixels a peon? A grunt? A spearman? You learn soon enough to distinguish them, but it’s confusing at first.

Warcraft 1, like its two sequels, is a real-time strategy game. You build a base, train units, gather resources for additional units and buildings, and send the units into battle. Unfortunately, compared to the sequels, the gameplay is really dated.

- You can only select four units at once. There is no area selection and you have to click them individually. If you lose your selection, you have to repeat the process, as there is no way to assign groups of units to hotkeys.

- Movement requires two button presses. You select the move command and then click on the destination. No right click movement. At least there are hotkeys.

- There is no attack-move mode. Pressing Attack and selecting a destination works the same as regular move, and your units will ignore enemy units until they stop.

- You can only construct buildings along roads, and only a certain distance away from your Town Hall. You can build roads (a mechanic removed in later games), and it seems you can build roads as far away from your base as you want, as long as they’re connected to existing roads.

- You only have one Town Hall, so when your starting gold mine is exhausted, you will have to send your workers across half the map, which bogs down already slow gameplay.

- Once you reveal a tile, it stays revealed and you can see unit movements across it. From Warcraft 2 onwards, once a part of the map goes outside your scouting radius, you only see the terrain there, not unit movements.

- Except for caster units, the two sides are only cosmetically different. Every unit and building except for caster units has an exact counterpart in the other faction, with the same stats (Peasant/Peon, Footman/Grunt, Archer/Spearman, Knight/Raider, Catapult/…er, the exact same Catapult).

The game feel is also kind of underwhelming compared to later installments. Most missions task you with destroying all enemy buildings and units, which means that even after you’ve razed the enemy base and killed their workers, you might have to spend a lot of time hunting the map7 for that last enemy footman you missed.

The variety of units is small compared to the sequels. Grunts are melee units, spearmen are ranged, raiders are heavy melee, catapults do splash damage (including friendly fire), necrolytes raise the dead, and warlocks summon daemons (who are really tough). As usual, your tech tree unlocks gradually over the course of the campaign.

There are thirteen missions in the campaign, all part of a single narrative. Let’s talk about…

The Story

The story is told entirely through the briefings at the beginning of each mission. One thing that is unusual for those who started with Warcraft 3 is that the briefings directly address you, the player, as a character in the story. You are an unnamed orc commander taking orders from War Chief Blackhand. TV Tropes, of course, has an article for this kind of character: you are a Non-Entity General.8

- You build six farms and a barracks in the Swamps of Sorrow. (That’s how they’re spelled in the first game. The map uses the name “Swamp of Sorrows”.)

- You clear out human resistance in the Borderlands of the Swamps of Sorrow, presumably present-day Deadwind Pass.

- For a change of pace, you’re given a mission without a base where you command a limited number of units. You’re told to descend into the Dead Mines and kill Blackhand’s daughter Griselda, who eloped with an ogre, and all her ogre minions. This mission, notably, takes place in the “dungeon” tileset, as opposed to the other two tilesets, “swamp” and “forest”.

- You assault human camps for two more missions. Notably, the second one has a non-standard game over: there is a conjurer’s tower on the human base that you’re asked to preserve, and if you destroy it, you fail the mission.

-

Plot twist! You exploit a flaw in Blackhand’s troop deployment, assaulting his castle at Black Rock Spire.9 Oddly enough, the briefing for this mission is delivered in the same third-person narration as always. But if previous orders came from Blackhand, who’s giving them now?

This is an interesting mission. Both campaigns, to ease the monotony of fighting the same enemies, have one mission where you fight your own faction. (Hilariously, the TV Tropes article for that is called Civil Warcraft.) The lore justifications for them, however, are completely different. This one establishes the backstabbing, opportunistic habits of orcs, where a leader ascends to power primarily by killing the previous leader.

The briefing for the next mission then tells you that the Shadow Council orders the assassination of Blackhand and elevates you to the position of War Chief. This is the only time the Shadow Council is mentioned in the entire orc campaign, and we can infer that it wields power above that of the War Chief, though, just like the manual, we’re once again not told what it actually is.

-

A wolfrider brings you news that Garona the half-orc spy has been captured by the humans and is held in Northshire Abbey. She has useful intel on human “magiks” (as it’s persistently spelled in-game), so you set out to rescue her.

This mission is a little odd, and highlights how the developers’ vision was too ambitious for the assets they had. Northshire Abbey is depicted as a underground dungeon, with branching caves. It’s populated by brigands, ogres, giant spiders and slimes, with no actual clerics in sight.

What’s even weirder is that although brigands have their own entry in the manual, which clearly says they’re outlaws, here they’re helping the other humans defend the abbey. Furthermore, this is the only campaign mission brigands appear in, despite it being a completely inappropriate environment for them. It’s like the manual writer, unit designer, and mission designer weren’t on the same page.

There’s some of that Warcraft 1 jank here, too. In addition to Garona, there are peons imprisoned across the map. You can rescue them, which is not visually indicated in any way, except that when you approach them, they get a scouting radius as they become your units without any change to their sprites. Of course they’re useless in this mission, except as a source of bodies for your necrolytes to raise, you dirty kinslayer. (Then again, kinslaying is perfectly par the course for orcs as they’re depicted in this particular game.)

Finally, Garona herself is found in the farthest away room. When your units approach her, she comes under your control — again, without any visual indication — and the mission ends when you bring her to the Hostage Rescue Zone™ near your starting position, indicated by arrows on the ground. Even more weirdly, despite having a unique sprite and portrait, Garona uses generic male orc voice lines.

- From this point on, it’s just you fighting human bases. You raze one human settlement behind a lake. Then you raze two human settlements, Goldshire and Moonbrook, on the same map.10 And finally, you face three human bases on the same map, with Stormwind Keep in the middle.

The humans in this campaign don’t have any unique named units.

The Finale

Your reward for completing the orc campaign is yet another block of voiced scrolling text, just on a different background.

With the decimation of the human forces, the sacking of their castle was a simple matter. They offered little resistance once you ran their weak leader through with your war blade and toppled his body into the moat. The taking of Stormwind has kept your warriors in good spirits, and the offerings of gold and jewels that they bring to you are ample tribute to your leadership. Wine flows like blood, and the smell of freshly cooked meat fills you with satisfaction as you begin your victory feast. The countryside is ablaze with bonfires as groups of battle hardened Orcs celebrate your dominion of this land with songs of war and victory. You have finally assumed your rightful place as ruler of this realm, and as War Chief of the Orcish Clans…

What new conquests will await you in this place? The Shadow Council has begun to bring you information concerning the lands across the great sea that are as yet untouched by Orcish rule. The Warlocks also seek your permission to resume their experiments with the portal, their intent being the subjugation of other worlds. With the power you now possess your choices are limitless - but these are choices for another time…

We get it. Orcs are evil and ruthless. Of note is that this victory text describes you killing King Llane, personally. Garona is not mentioned at all after the mission where you rescue her.

That’s our sequel hook — at least, for the orc campaign. The orcs have sacked the Kingdom of Azeroth, are victorious, and there are hints at new lands to conquer. This is a very bare-bones story, but one that will greatly affect the overarching plot of Warcraft from this point on…

Except for this additional wrinkle: the orc and human campaign tell completely different and irreconcilable stories. This is not Starcraft or Warcraft 3, where the campaigns follow each other and tell a single overarching story. The orc campaign tells one complete story that ends with an orc victory, and the human campaign tells a different, also complete story ending with a human victory. This is a conundrum that future installments will need to solve.

We’ll look at the human campaign next time, followed by some closing thoughts on this game.

-

Which, by the way, I recommend as a convenient way to buy games DRM-free and without bloated launchers. You get an installation .exe and can install the game wherever you want, on however many machines you want. ↩

-

In that era, storage space was expensive. A game that was supposed to fit on four 1.44 MB floppy disks simply couldn’t afford to store background music as raw sound data, even in the compressed MP3 format, let alone uncompressed WAV. The solution was MIDI, the digital equivalent of sheet music, which stores information about notes and instruments they should be played on. The MIDI file format allows composed music to be described very compactly, but it might sound differently depending on the synthesizer used to play it, and back in the MS-DOS era, you needed to have a sound card with a hardware MIDI synthesizer to hear it. These days, MIDI files are familiar to roleplayers through WoW’s Musician addon, which includes sound samples from many different instruments and mixes them together in software. ↩

-

There is, however, a unit editor, which allows altering game stats for units, buildings, spells, and technology upgrades. In Warcraft 2, the unit editor was merged into the map editor. ↩

-

It’s misspelled “Stonewind” on the map, but is consistently called “Stormwind” everywhere else in the manual and in-game. ↩

-

The lands extend to the north, east and south, and the Great Sea to the west, continuing the proud Tolkienian tradition of the Left-Justified Fantasy Map also seen in, say, the Forgotten Realms. ↩

-

Bill Roper was amazing. He was basically a one-man team, acting as a producer, composer, story consultant, voice actor, and whatever else a particular game needed. ↩

-

Which is visually very same-y, since it’s just the same terrain and forests over and over. ↩

-

Warcraft 2 would later retcon the orc campaign commander into a specific, and iconic, character. ↩

-

Represented in-game as just another orc base behind walls. Obviously, since this engine can’t do mountains. ↩

-

Unlike in WoW, here they’re practically neighbors. ↩

Leave a Comment